Prioritize Rail Connectivity in the 2018 California State Rail Plan

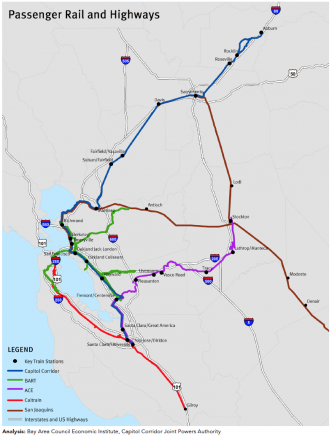

The entire megaregional transportation network would benefit from improved connections between its rail services. There are opportunities for investments in megaregional transit hubs in Livermore, San Jose, and Oakland, and they should be prioritized in the 2018 California State Rail Plan.

Use Megaregional Partners in Advocacy Efforts to Secure Funding; Simultaneously Explore Dedicated Sources of Infrastructure Finance

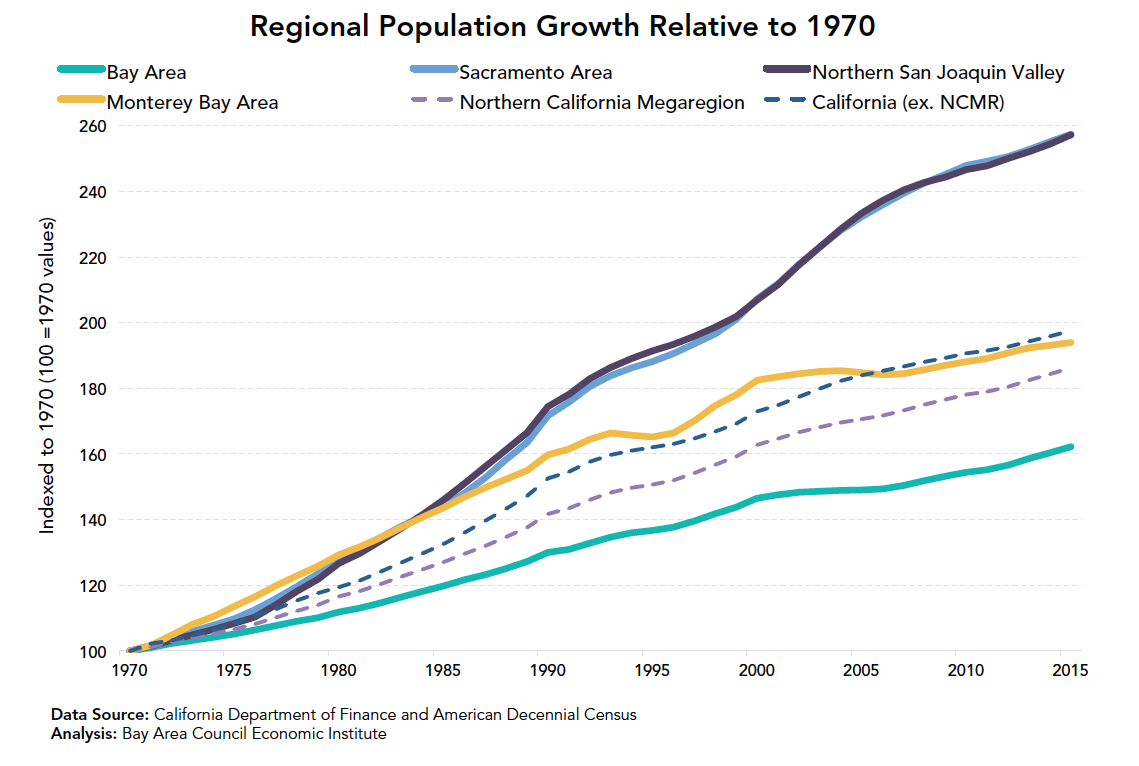

Infrastructure projects that span the megaregion require partnership and support from a megaregional group of stakeholders. These projects have extensive megaregional benefits—they take vehicles off of roadways, lower greenhouse gas emissions, and improve local economies by making them more attractive places to live and work. These benefits need to be recognized across the megaregion so that a coalition can support efforts to gain funding from Sacramento and Washington.

Funding sources for intercity passenger rail improvements might include tapping into the 40% of cap-and- trade funding that is currently unallocated. There should be a larger, on-going allocation of cap-and-trade funds to intercity and commuter rail services. While the Transit & Intercity Rail Capital Program receives 10% of cap-and-trade revenues each year, intercity and commuter rail services are not well positioned to compete against local and regional transit services for these dollars.

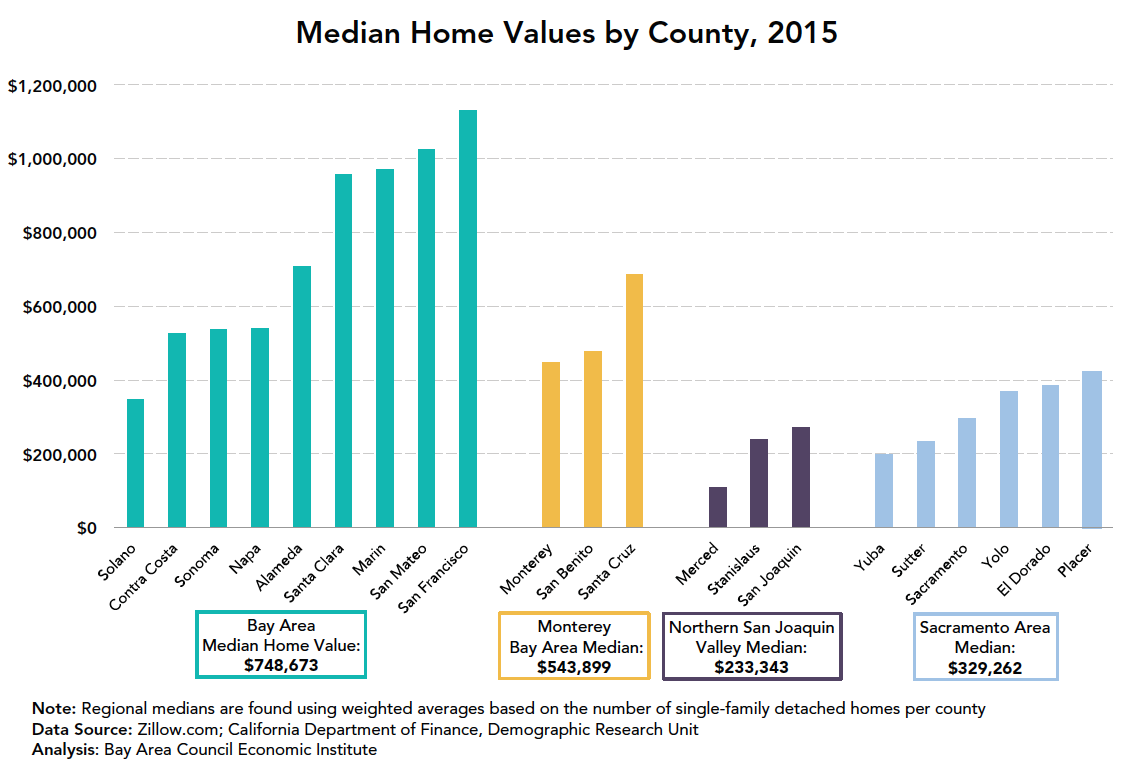

Streamline Housing Approval Processes, Especially for Projects Served by Transit

Governor Brown proposes that cities and counties require only “by-right” approval for certain types of housing projects. By-right approval can help to spur housing development across the Northern California Megaregion. Most importantly, it can facilitate higher density building near existing or planned rail stations that will give residents greater choice in where they live and work. Investments that increase train frequencies can have the effect of increasing demand for transit-oriented housing—this proposal can make that housing a reality. Additionally, the new stations that are built as a result of high-speed rail construction will more quickly promote economic revitalization, as developers will have more certainty of the types of building that will be approved.

Restructuring Goods Movement

Create a Structure for Passenger Rail and Freight Rail to Work Together

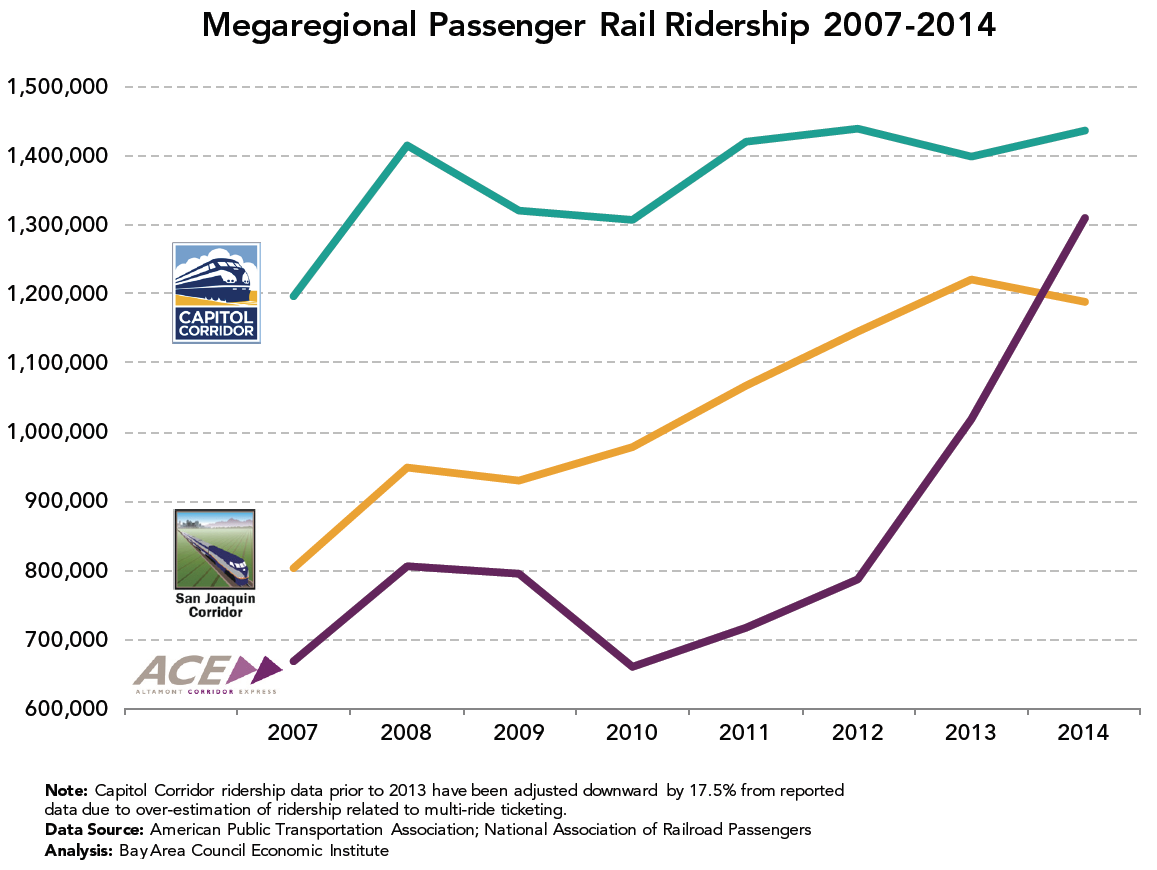

The issue of growing demand for freight and passenger rail is unsustainable. With the megaregion’s transit operators planning enhanced service and freight operators wanting to keep right-of-way available for their own future expansion, coordination between private freight operators and public stakeholders needs to have a more defined structure to reach mutually beneficial outcomes.

The Metropolitan Transportation Commission in the Bay Area, the Sacramento Area Council of Governments, the regional transportation planning agencies of the Northern San Joaquin Valley, and the rail agencies of the Northern California Megaregion have begun working together to advance megaregional planning. This partnership should be the focal point that acts as the point of contact for engagement with private rail operators going forward. It can ensure that passenger rail efficiently links the megaregion while freight operators continue to meet their market objectives.

Support Investments to Limit Environmental Impacts of Goods Movement

Many policies that can be implemented at the Port of Oakland have goods movement co-benefits that extend into the megaregion. For example, if more trucks load and unload at the Port of Oakland at night, truck traffic in the Northern San Joaquin Valley can shift away from peak travel times. An increased usage of technology in goods movement, such as improved tracking and coordination of truck arrival times at the port, can also limit the amount of time trucks spend idling while waiting to enter and exit.

The public sector should partner with private industry in making investments in goods movement. These investments might include more seamless rail connections and dredging to accommodate larger vessels in the Stock- ton shipping channel. The impacts of the $880 million investment planned at the former Oakland Army Base will also stretch across the megaregion with large public benefits. These types of policies and investments that have megaregional significance should be supported at a similar geographic level.

Coordinate Advocacy for Dedicated Goods Movement Funding

The Northern California Megaregion’s policymakers should help the state designate freight corridors of need. Projects identified in these corridors would be able to quickly access state funding when available and have the state’s support in efforts to garner funding from the recently-signed FAST Act, the federal government’s transportation spending plan. Future packages of freight rail investments supported by public funding might also be part of a deal that allows passenger rail to operate through dedicated rail corridors apart from freight traffic.