Economic Profile 2020: Is More Globalization or Localization in the Bay Area’s Future?

Will the Bay Area be more globalized or localized as a result of COVID-19?

The Bay Area is one of the world’s most globally connected economies. Home to several major global corporations, as well as a large foreign-born workforce and student pool, the regional economy has long benefited from connections outside of the U.S. Technology and innovation is a key part of this global story, as the region continues to attract businesses and talent from across the globe, making it a central location for companies to do business.

Globalization has been a clear benefit to the Bay Area, but how would the region operate if economies become more localized in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic or there is a shift in federal policies? The early days of the pandemic saw disruption of supply chains for companies that rely on inputs that come from overseas and momentum built around reshoring. As the country and region look for strategies to recover economically from the pandemic, global positioning will take on renewed importance. Federal policy, in particular toward China, and the evolution of corporate supply chains will play a critical role in determining the future path of the region. A recovery focused on localization and advanced manufacturing stands to be less of a benefit to high-cost regions like the Bay Area. A recovery that embraces globalization could again mean an era of rapid employment growth for the region.

Exhibit #1: The Bay Area is a leading exporter of technology, medical devices, biopharmaceuticals, and other products and services.

The Bay Area’s role as a leading exporter of technology and other goods is one way in which it has thrived as a global economy. California is home to three major trade ports – Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Oakland, which are also among some of the largest in the world. The Bay Area’s Port of Oakland is responsible for 99% of goods coming through Northern California by containers. Additionally, according to a 2019 study, the Port of Oakland supports over 84,000 jobs, generating an economic value of over $130 billion.

In the first ten months of 2020, the Port of Oakland imported 827,715 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) and exported 772,803 TEUs. While exports remained stable, the Port did see a 28% decrease in imports of TEUs between January and February of 2020. Import levels began to stabilize in April, with July seeing the largest number of imports from the Port in the year thus far at 96,420 TEUs.

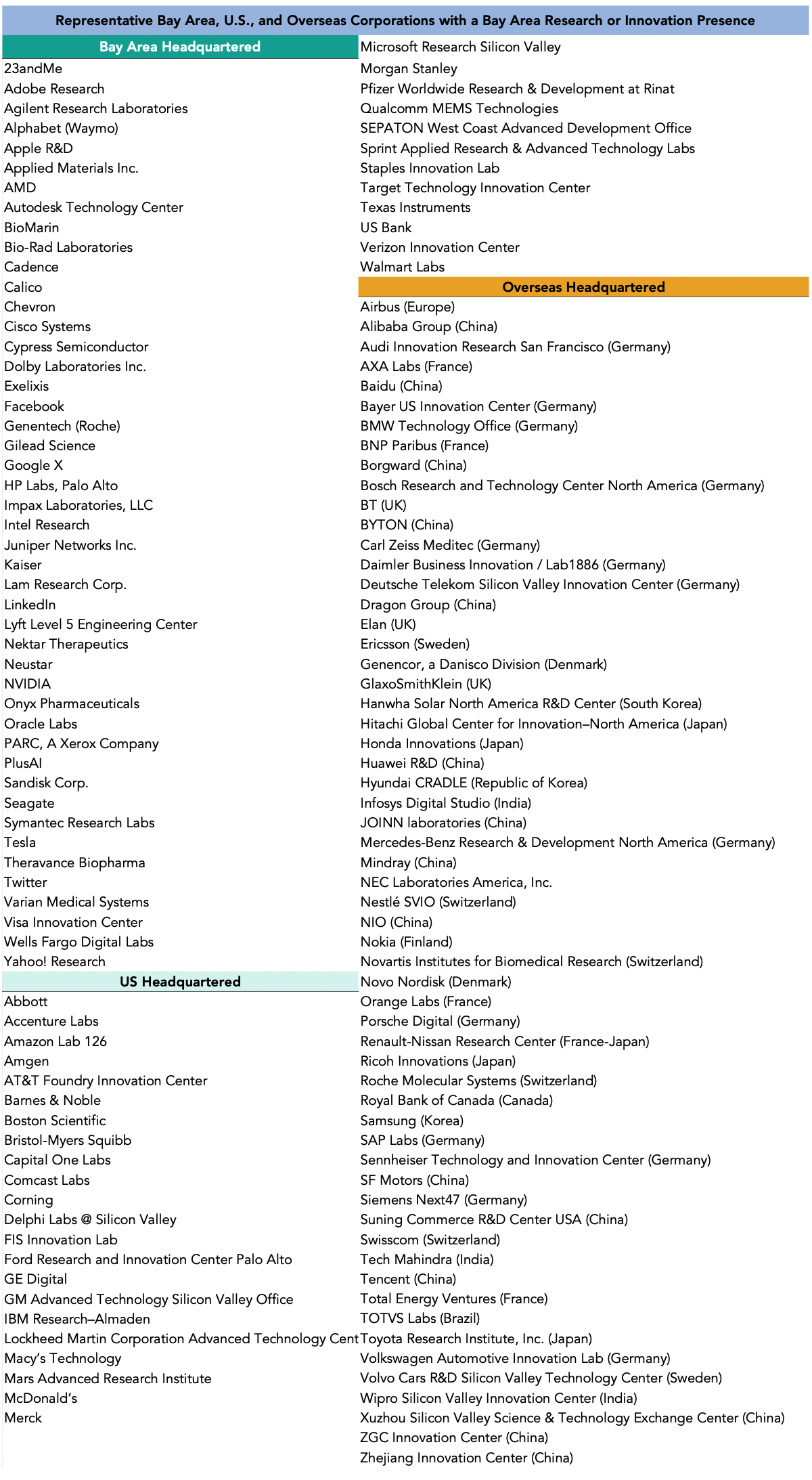

Exhibit #2: The Bay Area is home to the R&D centers of several global corporations, many of which are not themselves headquartered in the region.

In addition to the Bay Area’s trade prowess, the global nature of the region is also exemplified by its corporate R&D centers, many of which are operated by companies that are headquartered outside of the region and oftentimes even overseas. These R&D centers give companies an ability to participate in the Bay Area’s innovation ecosystem. As of 2018, the Bay Area had over a hundred R&D centers. An example list of several R&D centers operating in 2018 can be seen below.

Exhibit #3: In 2018, more than half of Bay Area billion-dollar startups were founded by one or more immigrants.

Much of the Bay Area’s innovation-driven economy is reinforced by immigrants. According to the National Foundation for American Policy, in 2018, more than half of the Bay Area’s startups with a valuation of $1 billion or more had one or more immigrant founders. This strong immigrant presence in the region is reinforced by the state’s overall demographics. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, in 2017, California had more immigrants than any other state, with the foreign-born population at 27% of the state’s total. The Bay Area counties with the highest foreign-born populations were Santa Clara (39%), San Francisco (36%), and San Mateo (35%) counties—notably also where the state’s concentration of technology workforce live and work.

Exhibit #4: 42% of the Bay Area’s STEM workforce is foreign-born.

Much like the founders of the region’s major startup and unicorn companies, the STEM workforce of the region also has a significant international component. According to a 2017 report by the American Immigration Council, approximately 42% of California’s STEM workforce was made up by immigrants in 2015. The demand for STEM workers, which has vastly increased in the Bay Area due to the region’s growing innovation economy, has led to progressively more immigration for STEM jobs. Between 1990 and 2015, the number of immigrants working in STEM in California grew from 509,000 to nearly 2 million.

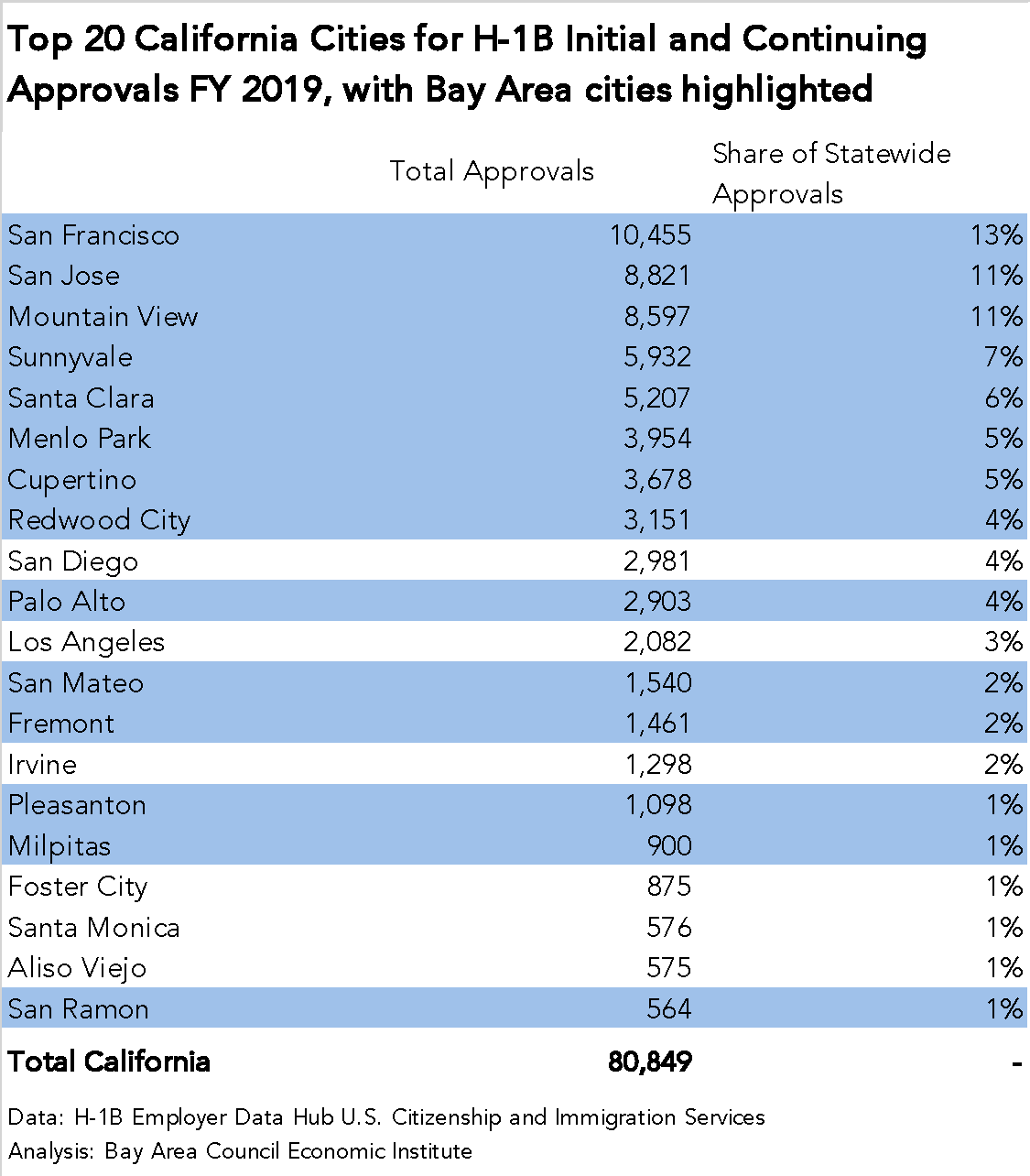

Exhibit #5: California has the most H-1B recipients out of any state in the nation, with new and continuing approvals across the state in FY 2019 totaling over 80,000.

Out of the top 20 California cities in terms of number of H-1B visas, 14 are in the Bay Area. Together these 14 Bay Area cities outpaced the State of Texas, which ranks second in the nation in terms of H-1B approvals. These 14 Bay Area cities had over 58,000 H-1B visa approvals in FY 2019 compared to 43,000 across all of Texas. The H-1B program supports employers who cannot obtain the needed business skills from the U.S. workforce by authorizing temporary employment to international talent. The concentration of these high skilled workers with H-1B visas in the Bay Area exemplifies the reliance that the regional economy has on the global flow of talent. While COVID-19 is impacting immigration currently, federal policy restrictions also may limit H-1B visas in the future. As such, trends in H-1B approvals in the Bay Area will be a key indicator of if the regional economy will emerge from the recession more or less globally connected than prior to the pandemic.

How will COVID-19 re-shape trends toward globalization?

COVID-19 is testing all facets of life and has revealed that the economy is globally dependent. Months into the COVID-19 pandemic, businesses have begun re-learning how to operate. It is possible, therefore, that the region becomes more globalized in the aftermath of the pandemic, particularly if businesses are able to maximize the use of virtual and online platforms.

Conversely, COVID-19’s shock to the world’s economic system could also mean a decline in globalization. Over time, the Bay Area has increasingly become a more expensive place to live, forcing companies and residents to find other cities to call home. Additionally, if manufacturing jobs are what jumpstarts the national economy, but California is too expensive a location for these jobs, advanced manufacturing hubs could grow elsewhere. Lastly, if national immigration laws do not reflect the unique importance and benefit that immigration provides to the Bay Area and U.S. workforce—for example, restricting the use of H-1B visas, then the region could lose out on the global talent that has enriched its innovation economy.