The Bay Area has been a global leader in health, pioneering advances from biotechnology to how healthcare organizations deliver care. However, like the rest of the United States, our costs are much higher than those in the rest of the world and our outcomes, in many areas, worse. We must work to build a system that creates more health at a more sustainable price to our society. And we must build a culture of health in which individuals are empowered to make healthy choices for their lives.

The following piece was written by Institute President Micah Weinberg in 2010, and despite its age, it still very relevant to the future of American health policy.

August 9th, 2010 — Last week, opponents of the new health care reform law cheered what they saw as two victories — a federal district court said a Virginia lawsuit against the reform could proceed, and Missouri voters overwhelmingly supported an anti-reform ballot initiative. Both targeted a key part of the reform law — the requirement that everyone have or purchase health care insurance.

As Sen. Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ken., put it, “The voters of Missouri sent a clear message that the federal government has no business forcing people to buy health insurance against their will. And I applaud them for it.”

So let’s say reform’s critics win and the “individual mandate” is killed. What then?

It’s far from clear that conservatives should cheer this outcome. Because it’s not just “Obamacare” that would be likely to fall, but the entire private market for health insurance as well.

Though you wouldn’t know it from listening to the talking heads on either side of the debate, federal health care reform was actually designed to strengthen the private health insurance market. It did so through the following deal: Health insurers would no longer be allowed to deny people for pre-existing conditions. In exchange, everyone would be required to have health care coverage.

Each part of this deal depends on the other.

If insurers can deny people for being sick, they have a strong incentive to offer policies only to the healthy. This vastly increases the number of people who are dependent on public programs or who simply have no way to pay for care. These costs get passed along to everyone else in the form of higher premiums and co-payments.

If insurers can no longer deny people for having an illness but there is no requirement to have coverage, people can simply wait until they fall ill before they buy insurance. This leads to increasingly sicker pools of people according to what is technically (and spookily) named an “adverse selection death spiral.” This is what’s happened in every state that tried to require insurers to provide policies to everyone who applies without requiring everyone to have coverage.

If you knock out either of the legs in health care reform, the private insurance market falls.

We cannot just go back to where we were before health reform, though, because even Republicans agree that health insurers shouldn’t be able to deny coverage to people because of pre-existing conditions. And none of the Republican ideas during health care reform — including the proposal that people should be able to buy insurance across state lines — would have addressed these issues.

If this round of reform fails, therefore, we’ll have to do something entirely different. But don’t hold your breath waiting for a system that relies even more heavily on the private market for health insurance.

In fact, the most likely thing that we will do is move toward a system like Medicare that is financed by the government.

It turns out that Medicare is extremely popular among seniors of all political persuasions, even tea partying ones. After all, the thing the town hall screamers were the most upset about was the idea that the program would be changed to institute “death panels.” This was a vicious smear that could not have been further from the truth. But it shows just how little appetite there is for changing the Medicare program in any way, even among members of the conservative right.

So people of all political stripes love to love Medicare, and they love to hate insurance companies. It stands to reason, therefore, that if we have to start over, we’ll build on what is popular rather than heading even further in an unpopular direction.

Conservative Republicans are free to continue their quest to undermine health care reform. But they should be careful what they wish for, because through their actions they may be the very people who finally lead this country to … a single-payer health care system.

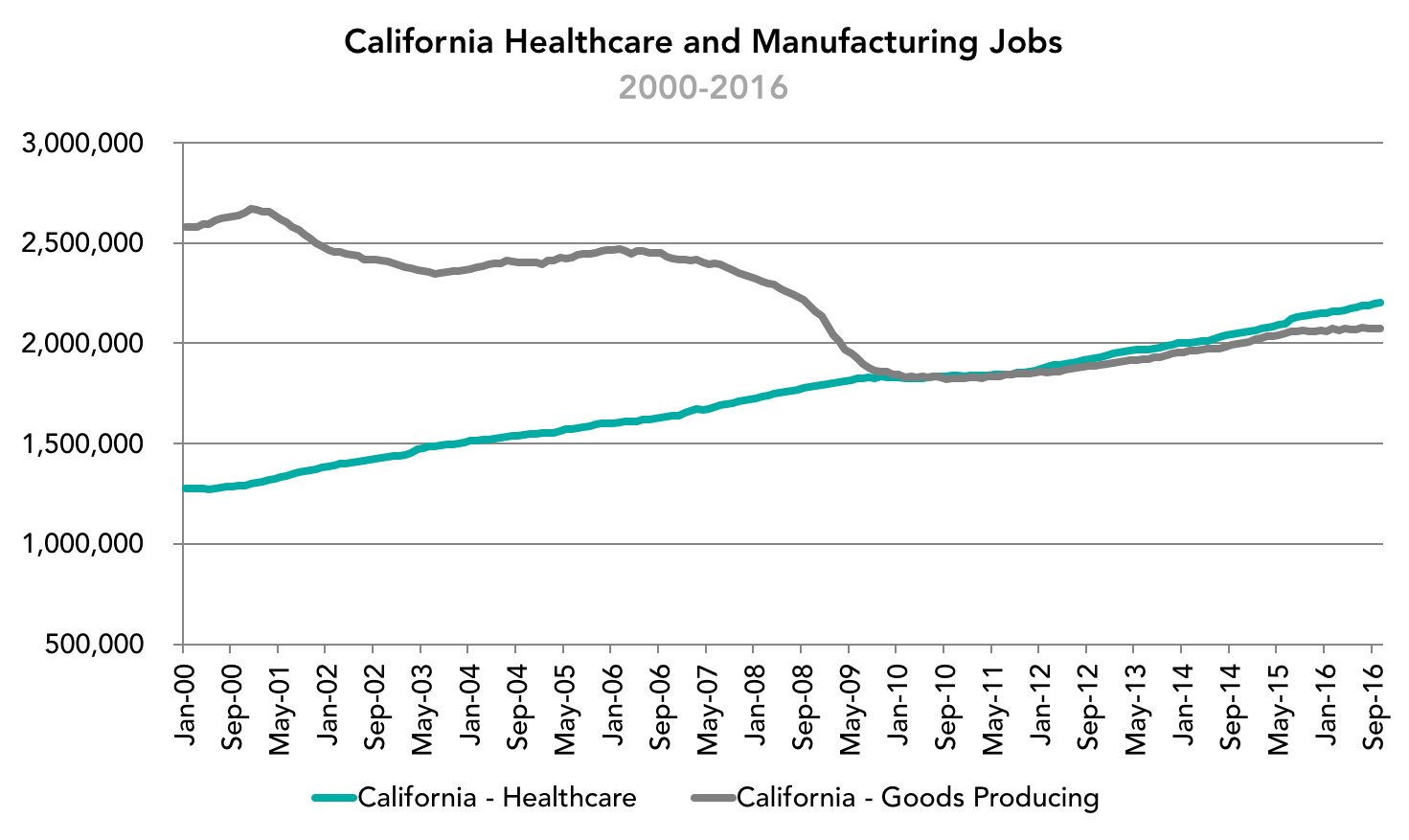

The presidential election focused on the disappearance of manufacturing jobs in the United States as well as the move to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which if it does nothing else, will dramatically decrease the amount of money the federal government spends on healthcare. A deeper dive into the relevant economic data raises important questions about these priorities at least as it relates to job creation. The chart below shows the trend for California that mirrors the trend in the nation: As manufacturing jobs declined over several decades largely driven by automation, they were replaced by healthcare jobs that are substantially more difficult to automate or offshore. There is reason to believe, therefore, that pumping more money, resources and attention into manufacturing at the expense of healthcare may be – for whatever other virtues this strategy may hold – problematic from the standpoint of job creation.

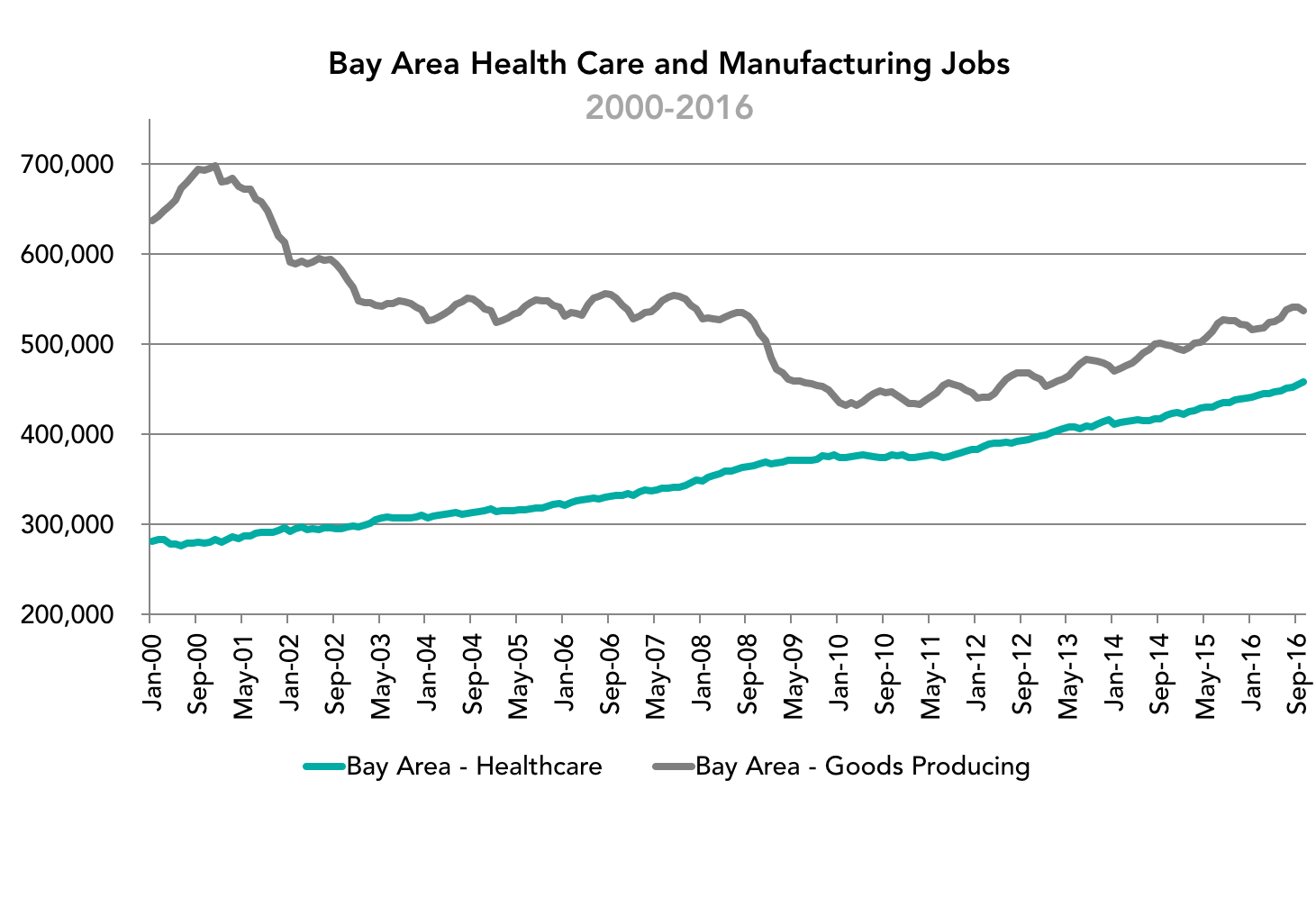

The trend in the Bay Area mirrors the trend in California and highlights the other missing piece of the conversation. Though manufacturing jobs are far below their historic peaks in the mid-20th century, there has been a slow and steady rebound of manufacturing employment in the region over the course of the past 5+ years. This is indicative of the increasing strength of the domestic economy during this time, and the emergence of export-driven high value-added manufacturing clusters in the Bay Area and throughout the nation. Pretending that manufacturing jobs are still in freefall, therefore, may lead to a belief that more aggressive anti-trade measures could prop up this sector of the economy. They would be much more likely, however, to choke off this rebound and impact not only these jobs but an economy that is producing a greater value of manufactured goods than at any other time in history.

Written by Micah Weinberg, PhD

In partnership with the March of Dimes Foundation the Bay Area Council Economic Institute unveiled the Cost of Prematurity to Business Estimator. Prematurity is the number one cause of death for newborns in the United States, with one out of every nine babies born premature each year in the United States at an average medical expense of twelve times that of a healthy baby. The event featured presentations from the Institute as well as from Dr. James Byrne, Chairman of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Santa Clara Medical Center; Tre’ McCalister, Principle at Mercer; and Dr. Maurice Druzin, Professor and Vice Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Stanford University School of Medicine outlining steps businesses and individuals can take and on the progress leading medical researchers are making.

Join the Institute for a summit on exciting recent advances in precision medicine. In addition to showcasing the scientific progress in this field, the summit will include a serious, high-level conversation about how to best deliver and pay for precision medicine to ensure maximum benefits to patients.

Simply put: an inefficient delivery system that unnecessarily restricts health professionals from practicing to the full extent of their training is bad for the economy and bad for business. Fully utilizing the role of nurse practitioners is one of the most effective steps that states can take to increase the supply of primary care providers.

Briefs and Analyses

- September 2014: Report (PDF: 45 pages, 1.9 MB)

- April 2014: Spotlight California (PDF: 2 pages, 683 KB)

- August 2014: Spotlight Kentucky (PDF: 2 pages, 753 KB)

- June 2014: Spotlight Minnesota (PDF: 2 pages, 417 KB)

- August 2014: Spotlight New Jersey (PDF: 2 pages, 312 KB)