April 7, 2025

Recent political and economic decisions, particularly tariffs, have strained relationships with allies like Canada, Mexico, Australia, and European countries, causing diplomatic fallout and economic uncertainty. In this article on Medium.com, Sean Randolph, Senior Director of the Institute, reflects on the declining strength of U.S. global alliances and emphasizes the long-term impacts of dismantling institutions and relationships.

November 11, 2024

The Trump presidency will reshape the United States relationship with the rest of the world. Changes from the current administration will be abrupt, with a long list of campaign promises revolving around ending the war in Ukraine, immigration reform, tariffs, and much more. In this article in the Silicon Valley Business Journal, Sean Randolph, Senior Director of the Institute, puts aside the strategic issues and details early takeaways on the economic side of the incumbent administration.

August 5, 2024

The worldwide shift of production is fully underway as companies with global operations diversify their sourcing and work to manage risk. A trend for several years, this has become a flow. A less hospitable environment in China and tensions in US-China relations are a driver, but so is the need to reduce dependence on any one country (a problem laid bare by China’s pandemic shutdowns) and a desire to bring production closer to home. In this article in the Silicon Valley Business Journal, Sean Randolph, Senior Director of the Institute, details the three prime destinations for production for the U.S. which include India, Mexico, and Southeast Asia.

June 25, 2023

As Mexico’s strategic importance to the U.S. grows, its newly elected president, Claudia Sheinbaum, has an opportunity to deepen the economic relationship and with-it prosperity in both countries. In this article in the Silicon Valley Business Journal, Sean Randolph, Senior Director of the Institute, details the vision and what the future can hold between the two nations and the greater North America.

September 6, 2023

June’s meeting between U.S. President Biden and India’s Prime Minister Modi advanced the U.S.-India connection to a new level. While the relationship falls short of an actual alliance and India and the U.S. may often differ, the alignment of national interests continues to deepen. In this article in the Times of India, Sean Randolph, Senior Director of the Institute, discusses the scope and breadth of cooperative agreements, mostly centered around technology, which has played an increasingly important role in the relationship

August 1, 2023

Europe and the United States are allies, collaborators — and competitors. Today, it is increasingly important that Europe and the United States look beyond competition to align their policies and capabilities around shared strategic goals. In this article in the SF Business Times, Sean Randolph, Senior Director of the Institute, examines these connections and details why Europe and the U.S. don’t see eye-to-eye on technology regulation, which is ultimately hurting both

June 23, 2023

India’s economic ties to the San Francisco/Silicon Bay Area are continuing to grow, led by the dramatic acceleration of India’s digital economy, the maturing and growth of its startup environment and the deepening geostrategic alignment between India and the U.S. In this article in the Silicon Valley Business Journal, Sean Randolph, Senior Director of the Institute, examines these connections and one of the greatest economic opportunities of the next decade.

April 18, 2023

U.S.-China tensions, supply chain vulnerabilities, reshoring, and other trends present a window of opportunity for North America. In this article in the SF Business Times, Sean Randolph, Senior Director of the Institute, examines the potential for North America if the U.S., Canada and Mexico can seize it.

August 26, 2020

China’s recent actions are fueling the fire for a further divide with the United States. With China’s leadership overstepping, other countries have taken notice and are beginning to push back . This article by Sean Randolph in The Times of India details how China’s actions will have repercussions on a global scale.

The Global Trade and Innovation Policy Alliance (GTIPA), a body of leading trade, economic and innovation think tanks around the world that work together to support growth through innovation and open market policies issued a statement are calling for policy measures to assure the supply of essential medical goods and to support the innovation that will enable future COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. Issued on May 18 to mark the opening of the WHO’s World Health Assembly, it addresses tariffs, export bans, the cross-border flow of epidemiological and clinical data, and the protection of intellectual property rights, issues which if not addressed could slow the global health response to COVID-19 and inhibit future research.

Sean Randolph, Senior Director of The Bay Area Council Economic Institute, recently published an op-ed in the San Francisco Chronicle outlining how the U.S.-China trade standoff has reached its current point, why a resolution has become so difficult to achieve, and how talks could eventually succeed. This op-ed builds on our previous reports, The Real Impact of Trade Agreements: How Trade Affects Jobs, Manufacturing, and Economic Competitiveness (April 2017) and Chinese Innovation: China’s Technology Future and What It Means for Silicon Valley (November 2017).

Additional reports by Sean Randolph:

The Real Impact of Trade Agreements: How Trade Affects Jobs, Manufacturing, and Economic Competitiveness:

Chinese Innovation: China’s Technology Future and What It Means for Silicon Valley:

Sean Randolph, Senior Director of The Bay Area Council Economic Institute, recently published an op-ed in the San Francisco Chronicle outlining the dangers America will face moving forward if it continues to alienate its global partners and abandon agreements it has not only benefited from, but has also utilized to maintain long-term, strategic relationships. This op-ed builds on our previous reports, The Real Impact of Trade Agreements: How Trade Affects Jobs, Manufacturing, and Economic Competitiveness (April 2017) and Chinese Innovation: China’s Technology Future and What It Means for Silicon Valley (November 2017).

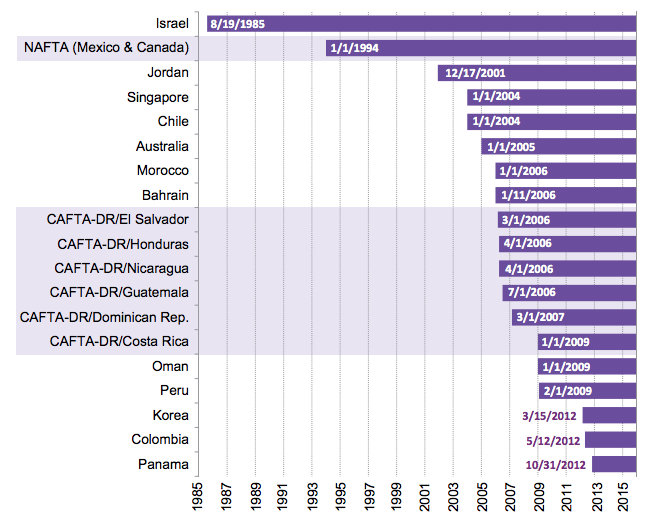

Between 1985 and 2015, the United States concluded 14 FTAs with 20 different countries. In its analysis, the United States International Trade Commission found that FTAs have a positive impact on real GDP, employment, and wages. In 2015, FTAs increased trade surpluses or reduced trade deficits with partner countries by 59.2% percent ($87.5 billion) and in 2014, produced tariff savings of up to $13.4 billion.

Additional reports by Sean Randolph:

The Real Impact of Trade Agreements: How Trade Affects Jobs, Manufacturing, and Economic Competitiveness:

Chinese Innovation: China’s Technology Future and What It Means for Silicon Valley:

As the premier global center for technology and service innovation and a major center of higher education, the Bay Area powerfully shapes and is shaped by the global economy. The Institute continually investigates how the Bay Area serves as an important business and cultural hub by being globally connected through foreign direct investment, links to other technology regions, large numbers of foreign students at its universities, and a globally diverse population. The level of connection between the Bay Area and China is unique in its depth and breadth, and China’s technological capacity in the coming years will profoundly impact not only competition and market opportunities in China, but global competition as well. The Bay Area’s Economic ties to Europe date back to California’s Gold Rush, and Europe continues to be an essential partner in shaping the region’s economic future. Cross investment with Europe is larger than with any other global region.

Institute Senior Director Sean Randolph offers initial analysis of the historic vote in Britain to exit the European Union and its impact on the Bay Area economically.

The full implications of Britain’s decision to leave the European Union remain uncertain, but some are foreseeable. In the short term equity markets – particularly financials – will be hit, with new uncertainty in global financial markets. Economists predict that Britain’s departure will cloud the prospects for its economy, leading to a recession. If this occurs Bay Area companies may be impacted, since Britain is one of the region’s leading trade and investment partners. A significant devaluation of the pound and strengthening of the dollar could negatively impact exports in particular.

The long term implications are less predictable, but could be large. London – where a number of Bay Area banks base their European operations – will see its status as a global financial center diminished, as institutions doing business in Europe shift their operations. Other US companies with European headquarters in London will also shift resources to the continent. This could benefit other European centers, such as Germany. Companies located in the UK will find it more difficult to attract European and other talent, with significant implications not only for large companies but for startups as well.

By raising a border between Britain and Europe, the regulatory cost and complexity for Bay Area companies conducting business in Europe will increase, as the efficiency of what is now a single market in Europe for trade in goods is reduced. Business and leisure travelers between Europe and the UK will likely face new visa requirements.

Within the EU, Britain has been a voice for market policies similar to those in the US, but will no longer be at the table. This could impact future policy direction in the EU in ways that are not helpful to Bay Area technology and other global companies.

At the political level, anti-EU and separatist movements across Europe will be encouraged. Britain’s exit will encourage sub-national entities seeking independence from their countries to make a break. Scotland, where an independence referendum only narrowly failed in 2014, may move first, and Catalonia in Spain may not be far behind. The creation of a border between Northern Ireland (which is part of the UK) and the Republic of Ireland raises further issues.

In the end, Britain’s departure points toward a less integrated, more divided Europe, and increased business costs. The growing strength of populist movements in both Europe and the US will add to the growing political pushback against trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership with Asia and the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with Europe. Many of the issues that Brexit raises will be worked out in Britain’s negotiations with the EU, and Britain will remain an important long term partner for the United States. What is also clear, however, is that in the post-Brexit environment the economic globalization on which much of our recent prosperity has been based is open to question.

(Image from Flickr used Davide D’Amico)

Long before the words “Grexit” or “Brexit” entered the popular lexicon, the economic news out of Europe was difficult. Since the 2008–9 recession, Eurozone countries have been treading water, bobbing up and down in the wake of the economic storm: falling into recession in spring 2008, rising out in spring 2009; falling again in late 2011, rising again to growth of 1 to 1.5 percent in 2014 and 2015. Across the Eurozone, success is piecemeal and has varied by region and country. In 2015, Germany’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 1.5 percent, while Italy’s economy followed two negative years with 0.8 percent growth; resilient Poland, one of only two European Union (EU) member states able to avoid the Great Recession altogether, grew by 3.5 percent.

Whatever the metric or perspective, much of Europe has experienced a lost decade. With punishing austerity and high debt-to-GDP ratios in many countries, and slow growth across the board, how can Europe find its way again? Trade, consumer spending, and business investment—which have seen muted growth at best—are the traditional routes to economic recovery. But while Europe struggled, the global economy shifted to a more abstract foundation: innovation, especially digital innovation, from which trade and investment follow.

Innovation can be either incremental or transformative. Incremental innovation—the improvement of an existing process—is important to creating value, but by its nature it is often about building on existing creations; its returns are less explosive, but often are more stable. Transformative innovation, as its name suggests, can be game-changing, causing disruption of existing industries and processes, creating new industry leaders, and sometimes fundamentally changing the way people live. While Europe is rich in both human capital and technology and boasts many highly competitive international companies (Siemens, SAP, Philips, Bayer, and Ericsson, to name a few), the innovation stemming from these sources tends toward the incremental. Europe simply is not generating transformative innovation at a high level. With a few notable exceptions (e.g., Spotify, the music-streaming giant founded in Sweden), the nations of Europe are failing to generate and grow new cutting-edge technology companies.

By a range of measures, Europe is losing ground in the technology industries that are reshaping the world’s economy. A 2014 report by business consultancy A.T. Kearney suggests that Europe’s high-tech sector is actually in decline. According to the study, only 9 of the 100 top global information and communications technology companies are headquartered in Europe, a number that is falling due to mergers and acquisitions and faster growth by Asian and U.S. competitors. European spending on research and development (R&D) as a percentage of GDP lags both the United States and Japan, and of the world’s 13 largest patent-producing companies, only 2 are based in Europe. Digital commerce is a similar story. CB Insights reports that from 2010 through the first half of 2015, just three markets—the United States, China, and India—accounted for 62 percent of global venture deals and 71 percent of global funding for e-commerce. Germany and the United Kingdom were major markets, too, but at a fraction of the scale.

These data reflect activity by large companies at the top end of the food chain, but Europe’s innovation challenge goes deeper. In today’s fast-moving tech industry, smaller, more nimble companies are in many cases able to innovate more quickly than larger, more established corporations—including companies with substantial R&D budgets. The capacity to generate and grow new entrepreneurial enterprises is the proverbial engine in the global economic race. Recognizing this, communities throughout the world, including many in Europe, look to the place that often is thought of as synonymous with transformative innovation: the San Francisco Bay–Silicon Valley region. Comparing Europe, which led the global economy for centuries, and the surging economy of the greater Silicon Valley, illustrates Europe’s challenge and points to possible paths forward.

The Silicon Valley Standard

The economy of the San Francisco Bay–Silicon Valley region is driven by technology, drawing on an ecosystem that supports research, innovation, and technology commercialization. Patents offer one measure of innovation: the region accounts for 16 percent of all U.S. patents, far more than any other metropolitan area both in total numbers and in patents generated per million residents. Risk capital is another. Historically, roughly one-third of all venture investment in the United States has flowed into the Bay Area. In recent years, this share has grown, as the venture capital industry has consolidated into a small handful of cities. In 2015, Bay Area companies received almost half (46.5%) of all venture investment in the United States, reflecting both the concentration of venture firms in the region and an opportunity-rich environment of startup and early-stage companies.

The foundation of the Bay Area’s disruption economy is a massive research-related corridor. Major universities, national laboratories, and other R&D facilities are open to collaboration with industry. The area’s highly developed legal and financial services sector has deep experience in intellectual property, finance law, IPOs, and specialized industry needs. And it is home to an archipelago of incubators and accelerators that nurture younger companies, supporting them in a collaborative environment where they can engage with industry experts, investors, and other entrepreneurs. Equally important is the connective tissue between these pieces. There’s ambition to create global businesses, an extraordinary willingness in the business and entrepreneurial community to assume risk and accept failure, role models who have succeeded as entrepreneurs and are prepared to mentor others, and a highly networked business environment that enables people and ideas to overcome institutional barriers with relative ease and speed.

In the aggregate, the region’s unique array of assets has helped to create and nurture global titans, including Google, Apple, Facebook, and Twitter, as well as niche disruptors like Square, Uber, and Airbnb. Behind them, a mass of even newer companies and younger innovators follow, promising to disrupt the disruptors with ideas and impacts that are impossible to predict. This combination of ambition, resources, talent, and success has organically created a global brand for Silicon Valley and the San Francisco Bay region — and has made the region into something approaching a movement.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the magnetism of the Valley/Bay Area attracts talented, educated, and ambitious people from around the world. In this expat community, no region enjoys greater representation than Europe. Large European multinational companies are developing partnerships with large Bay Area tech companies, scouting emerging technologies, and looking for startups whose technologies or strategies either threaten or support their business models. Often, their global innovation teams are based in the region, working to translate its more open, nimble style of innovation back to their European headquarters.

Even more interesting than the presence of European corporations is the large-scale migration of European entrepreneurs to the region. More than 300 European startups and early-stage companies may be operating in or visiting the region at any given time. They come from virtually every country, are supported by an extensive network of European-oriented incubators and accelerators, and benefit from the peer networking and advisory services offered by European business organizations and their governments through consulates and dedicated innovation offices. The companies that succeed become mini-multinationals: the U.S. operation sources capital and handles marketing, while the European unit continues to employ the lion’s share of engineers, who are high-quality and cheaper to employ than their Silicon Valley counterparts.

Many of these immigrant entrepreneurs represent the best of European startup talent, and made it to the Bay Area through selective, competitive processes. They are where much of Europe’s future growth could and should come from, so it needs to be asked: what pulls them toward California and the Bay Area and, equally important, pushes them away from Europe?

Confronting Europe’s Challenges

Overall, Europe’s environment for startups is less desirable than that of the Silicon Valley–Bay Area because of differences in finance, scale, and culture.

Although the European community can claim a modest number of angel investors, Europe’s venture sector is underdeveloped. The total pool of venture capital invested in all of Europe in 2014 was $8.8 billion — roughly one-sixth the amount of that in the United States ($52 billion). European governments have stepped in to fill the void, providing the largest single source of venture funding (roughly 40 percent), followed by banks, corporations, and funds of funds. And many of the managers of European venture funds are bankers, not entrepreneurs. In the United States, most venture capitalists have started businesses themselves, and 90 percent of venture investment comes from private sources. Different sources of venture investment lead to fundamentally different levels of institutional engagement and mentorship. Private investors who have started companies and have their own money on the line are likely to take a much more hands-on approach supporting the companies in their portfolio. One implication of this pattern is that when European startups need serious risk capital, many look to the United States, and to the Bay Area in particular.

As a related driver, large European companies typically grow and innovate internally. American technology companies have developed strategies to grow by acquiring smaller firms. For European entrepreneurs aiming to see their businesses acquired, the United States therefore offers a far more promising environment. Add to this the fact that there are few places in Europe where IPOs are an option to exercise, and pressure builds for ambitious European startups to seek opportunity elsewhere.

Many European countries produce innovative businesses and entrepreneurs, but lack the market scale to grow them into global companies. Despite the single European market for goods, there is still no single EU market for services. Regulatory, tax, and labor policies remain the prerogative of national governments, which means that small companies hoping to grow beyond national borders face a multitude of varying regulations that multiply their costs. This problem of scale applies to venture capital as well, as there is no “European” venture market and investment is mostly at the national level. This means that a startup in Italy may draw on whatever risk capital is available in Italy, but is unlikely to attract investment from France. For many startups, the cumulative effect of all of this is that when they want to reach a global scale, they cannot achieve it while staying in Europe. Instead, many come to the Bay Area, expanding into the U.S. market first, then rolling out internationally.

Capital and scale are the biggest business-side challenges, but culture cannot be ignored. Negative attitudes toward risk and failure can discourage entrepreneurs and inhibit their ability to find new investors if their first endeavor fails. By contrast, the most American startups live by a different mantra: “fail early and often” (or, as Facebook famously implored its staff members in its early years, “move fast and break things”). In much of Europe, generous welfare states often translate into high tax rates at upper income levels—the top marginal rate in the United States is several points lower than the top rates in the EU’s five largest countries—which suggests negative attitudes toward wealth and discourages entrepreneurs from building businesses there. Overregulation further raises the barriers to entry, while in some countries rigid labor laws make it difficult to hire and fire employees with the flexibility needed in a volatile and uncertain business environment.

Does this mean that Europe has lost the innovation game and will fall further behind? Not necessarily. There is tremendous variation at the national level in Europe. Some small economies like the Netherlands stand out. Nordic countries in particular have shown impressive innovative capacity, particularly when measured by the proportion of their small populations to the number of globally significant companies with Nordic founders. Some Eastern European economies, such as Poland and Estonia, also show energy. Germany has a base of engineering and advanced manufacturing capacity that can be leveraged for growing applications in the Internet of Things. London and Berlin have emerged as important startup hubs with significant numbers of investors. In cities throughout Europe, incubators and accelerators with a look and feel much like those in the United States are sprouting up.

Promising partnerships between European and Bay Area resources already exist, and could prosper further in an innovation-friendly European service market. Looking to the future, partnerships between U.S. and European accelerators can help to anchor growth on both sides of the Atlantic, enabling more young companies to be successful faster. Negotiators in the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment talks can address barriers to the growth of small and medium enterprises. Plans have been announced for a Capital Markets Union, which can help but will take time to implement. By reducing regulatory fragmentation, the EU’s goal of creating a single digital market offers another opportunity to reduce barriers to tech growth internally and with the United States — if it doesn’t degenerate into a digital “fortress Europe.”

With a deep base of talent and strength in both manufacturing and design, Europe is rich in innovative potential. To generate change, however, it must quickly address the challenges of finance, scale, and culture. National governments (and the EU itself) are increasing their support for technology research and startups; European venture funding for tech is up. Cultural attitudes in Europe toward entrepreneurs (and risk and failure) are starting to change, and American venture capitalists are rediscovering Europe as a place to invest.

But innovation is also about speed, and it remains unclear whether these changes will happen fast enough to spur rapid company formation and growth, or home-grown companies with global reach. Disruption will occur, one way or the other—either Europe will be causing the disruption, or it will be disrupted, perhaps permanently.

Much of the news in international trade lately has been about the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a free trade negotiation of the United States with 28 Asian countries. Less attention has been given to the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (or TTIP), a parallel agreement with the 28 members of the European Union.

TPP is important, but TTIP merits equal billing. Despite a lackluster recovery from the Great Recession, Europe’s GDP, per capita income, personal consumption, exports, imports, and inward and outward foreign investment all exceed TPP levels in TPP economies. This is mirrored in the Bay Area: Europe in the largest foreign investor in the region, and there are more business affiliates here from Europe than from Asia—including China, which is not a TPP party. Bay Area businesses also have a larger presence in Europe than in Asia. Trade took a hit in the last recession, but could surge again if TTIP is successful.

What would TTIP do? Like other large trade agreements it would reduce tariffs, but it’s more innovative focus is on regulation. The US and Europe both have high regulatory standards, and while their approaches may vary, they tend to be comparable and achieve similar results. Today, companies on both sides of the Atlantic need to undergo compliance procedures twice, at considerable expense. For example, regulations governing the design of an auto bumper or steering wheel may differ in their details but produce equivalent levels of safety. But what if those standards were harmonized, or what if both sides simply recognized the standards and procedures of the other? Enormous resources saved, and costs wrung out of the trading system.

There’s another plus—because Europe’s environmental and labor standards are similar or even higher than ours, TTIP should be an easier sell in Congress than TPP.

A recent report by the Atlantic Council and the Bertelsmann Foundation estimates that the resulting growth in trade—particularly for small and medium sized businesses—could generate 75,000 new jobs in California alone. There’s also a strategic dimension to the talks. As democracies with advanced market economies, the US and Europe share common values. Russia, which doesn’t want to see strong US relations with Europe, is pouring money into Europe to support groups opposed to TTIP. In today’s geopolitical environment, TTIP has political as well as economic dimensions.

A final agreement may not be sent to Congress until after the next election. But it’s not too early to focus on TTIP and the progress of the talks. Like all trade agreements, it will be intensely debated and businesses and others in the region should be engaged. The fact that TTIP and TPP are in active play, both with enormous consequences for the region and the state, should remind us that our economic chips are stacked in Europe as well as Asia.

Trade, Investment and Invention

Economic Ties between Japan and the San Francisco Bay Area date back 150 years, to when the first diplomatic mission from Japan to the United States arrived in San Francisco. Since then, both Japan and the Bay Area have developed into two of the world’s leading technology hubs. This briefing paper continues the Economic Institute’s series of reports on the region’s business and economic links with major global partners.

Made for Trade

The revenues of Bay Area companies increasingly come from global markets, and the Bay Area economy is intricately linked with global trade and financial flows. The Bay Area is on the cutting edge of technology, innovation and finance, handling $25 billion in exports in 2013. As technology continues to increase as a percentage of global trade, the Bay Area is well positioned to export to expanding future and emerging markets, especially in Asia. A report commissioned by HSBC in 2014 looks at international trade activity in the Bay Area, with a particular focus on technology, China, and the internationalization of China’s currency.