Explore the traffic tracker here.

Each month, the Bay Area Council Economic Institute compiles data from the region’s 7 state-owned toll bridges, as well as ridership data from AC Transit, BART, Caltrain, Golden Gate Ferry, Muni, WETA, and VTA, to better understand how transit agencies are faring compared to bridge crossings.

Last update: February 2025

Note: Updates are made at the end of each month for the prior month’s data. Additionally, most transit agencies (aside from BART) are lagged by one month in their public data release schedule.

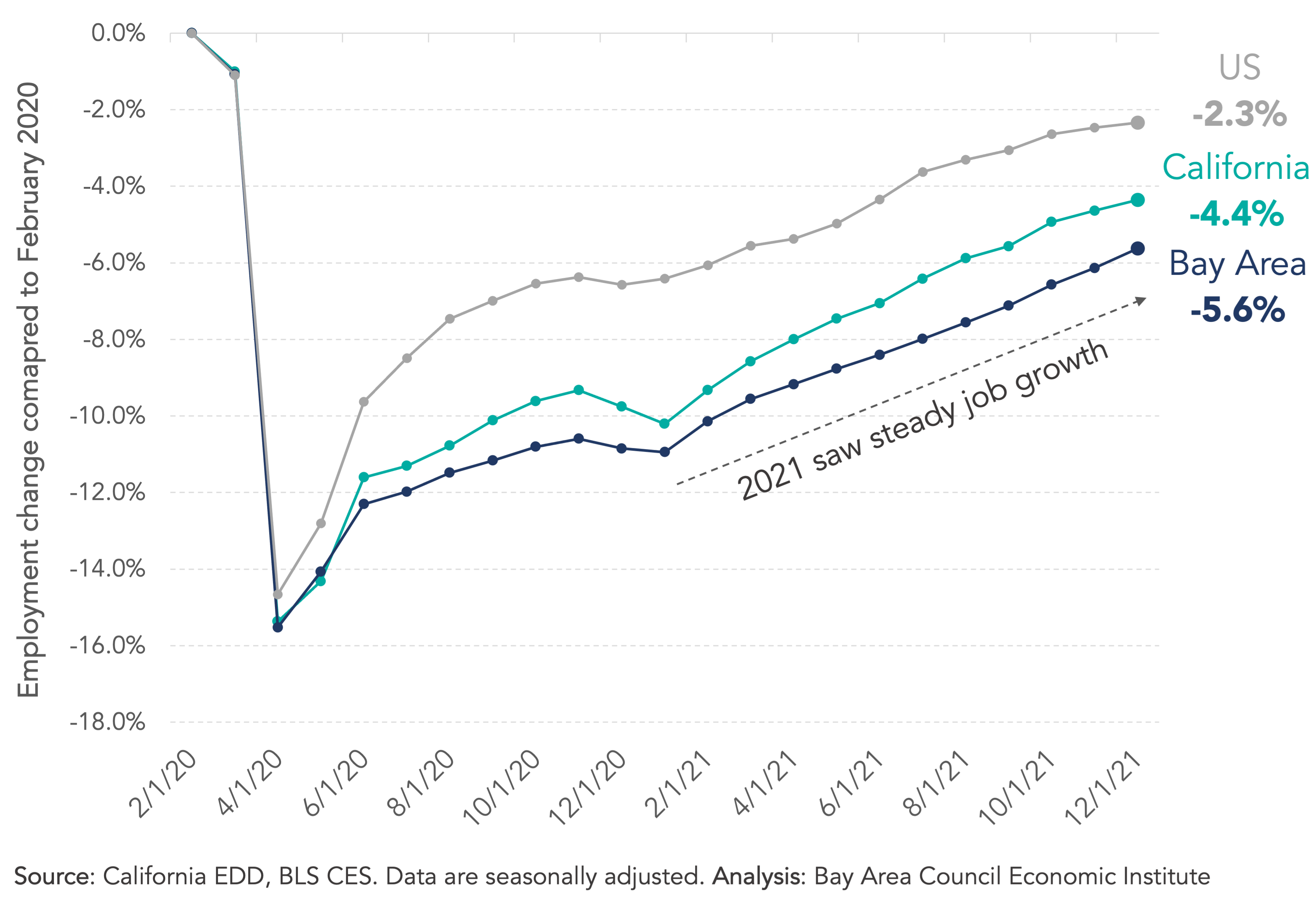

New data for December 2021 show modest gains in employment for the Bay Area, California, and nation overall, ending a year of slow but steady job growth. While the first half of 2021 was marked by vaccine approvals and a reopening economy, the second half was marked by the Delta and Omicron variants, bringing forth new challenges to achieving a full recovery. As we enter 2022, the Bay Area is still down 5.6 percent of pre-pandemic jobs, and its job recovery rate continues to lag behind the state and nation.

Fig 1. Employment change in California and the Bay Area since February 2020

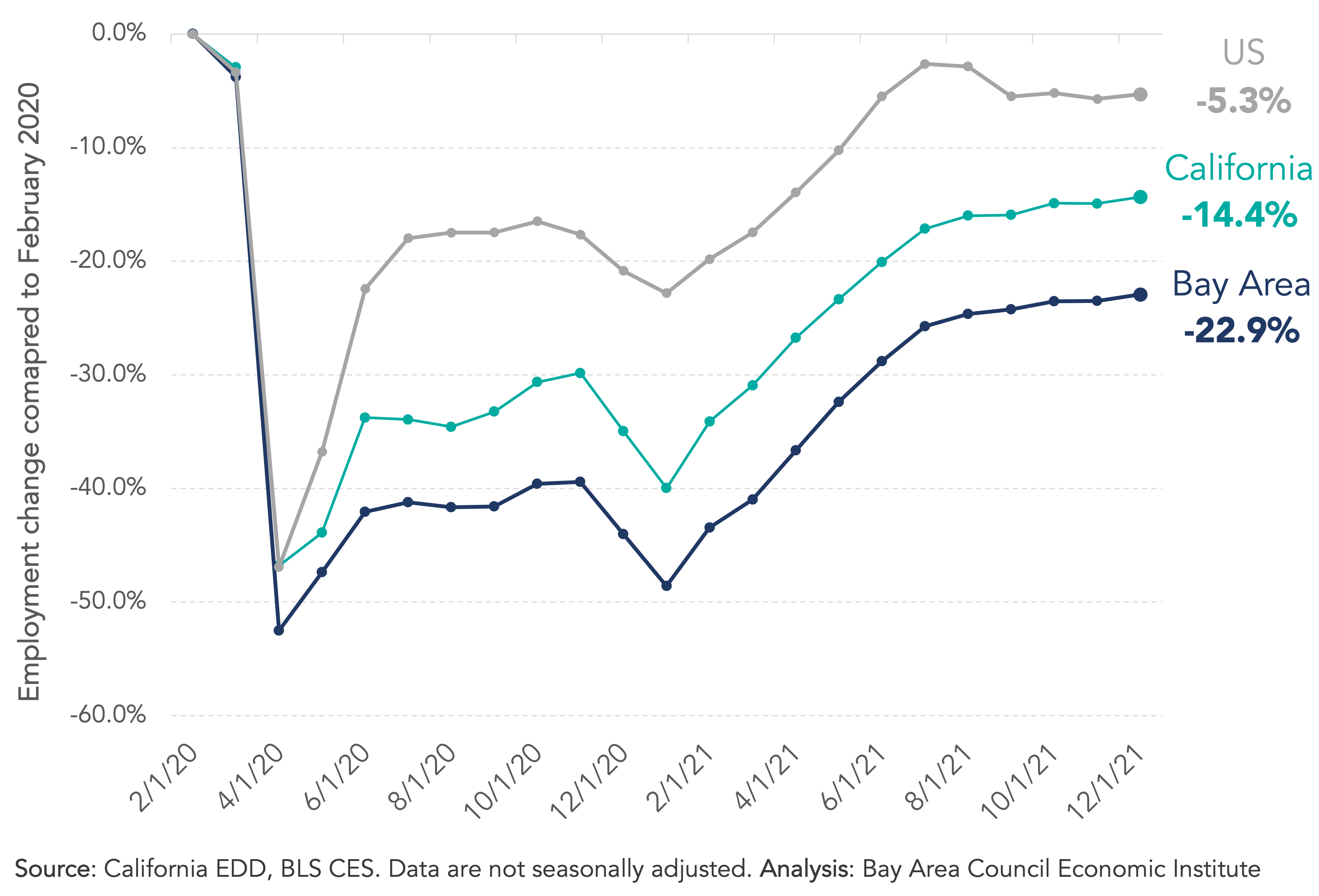

The gap between California and the Bay Area can be largely attributed to massive regional job losses in the leisure and hospitality sector (restaurants, hotels, arts, and spectator sports). Losses in this sector have accounted for 44 percent of the region’s overall 231,400 jobs deficit. And despite significant growth in this sector as businesses reopened during the first half of 2021, growth plateaued during the second half of the year, leading to an enduring deficit of 23 percent. December data do not reflect the full picture of the Omicron variant. As January employment is made publicly available, we may see even greater job losses in leisure and hospitality.

Like many large urban metro areas, the Bay Area has a high share of service economy jobs and a high share of office jobs. In many instances, the service economy relies on that office economy, and to some extent the tourism economy, for its revenues. With low domestic and international tourism, and all signs pointing to a “return to office” that includes far fewer in-person work days, the region’s service economy will struggle to return to its pre-pandemic employment levels in 2022. Even as recovery occurs, some service workers have dropped out of the labor force or moved outside of the region, so hiring in the sector will remain a challenge.

Fig 2. Leisure and hospitality employment change in California and the Bay Area since February 2020

The region’s recovery into 2022 will hinge on growth in other sectors to outpace the losses in leisure in hospitality. Longer term recovery will also hinge on better supports for women and caretakers in the workforce. A continued lack of child care was a key driver for mothers exiting the labor force — nearly one million mothers left the workforce nationwide, compared to half that number of fathers. Regional labor force recovery and growth in the long-term hinges on key policy reform and legislation, like paid family leave, to support women and other disproportionately affected groups’ return to the workforce.

As remote work continues, commercial vacancy rates in many urban areas remain elevated. However, high vacancy rates have yet to put significant downward pressure on rental costs. While the space may be available for new companies to move in and for established companies to grow their footprints, price remains a challenge. The high cost of real estate plus high labor costs in the region have pushed many companies to hire in other geographies or for fully remote positions. That has resulted in the Bay Area producing some the slowest job posting growth during the pandemic of any metro area in the US – a cause for major concern about the region’s ability to re-produce its leading level of employment growth.

As of November 2021, San Francisco’s labor force – defined as those employed or looking for work – is still down 78,000, or 3% from pre-pandemic levels. Our region’s recovery remains one of the slowest compared to other large metro areas, despite accelerated gains over the last six months due to lifted restrictions and rising vaccination rates.

At its peak in May 2020, the Bay Area lost 7 percent of its labor force. Women were disproportionately affected, dropping out of the labor force at a faster rate than their male counterparts. A continued lack of child care was a key driver for mothers exiting the labor force — nearly one million mothers left the workforce nationwide, compared to half that number of fathers. Regional labor force recovery and growth in the long-term hinges on key policy reform and legislation, like paid family leave, to support women and other disproportionately affected group’s return to the workforce.

The following presentation contains seven months of survey results. Each survey was sent through the Bay Area Council Employer Network; a group of over 100 employers who signed up to participate in the survey. Employers were recruited to participate in this Employer Network over the last several months. Each survey had employers from all nine counties and across sectors; however, the data is not intended to be representative of all employers in the Bay Area.

If you know of employers who would like to participate in this Employer Network to have a voice in the region’s reopening plans, please encourage them to register here or reach out to Bay Area Council team member Kelly Obranowicz at kobranowicz@bayareacouncil.org.