Strategies are being developed to provide capacity and reliability enhancements in the transbay corridor. With significant investments, BART can increase train frequency, WETA can provide increased ferry service, and AC Transit can run buses across a dedicated Bay Bridge bus lane. Even with these investments, BART’s transbay crossing is projected to hit absolute capacity (i.e., full length trains, filled to capacity, running at the greatest possible frequency) within the next two decades under conservative growth assumptions.

Insufficient capacity is one piece of the congestion challenge, but BART’s transbay bottleneck drives additional threats to the Bay Area’s connectivity. First, aging BART infrastructure and the region’s heavy reliance on the transbay tube to carry passengers into core urban areas contribute to declining service reliability. Problems such as a mechanical door failure or a malfunction of a rail switching device can create commute delays that extend for hours and can snarl regional transit and roadway networks. Second, the need to keep the transbay tube open to commuters limits BART’s ability to conduct routine maintenance and major repairs, both of which are required for infrastructure that is four decades old.

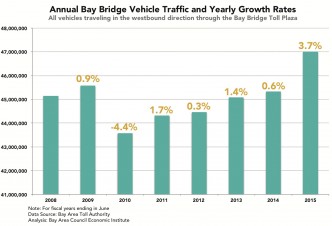

The regional transportation system also has few built-in alternative transbay options if a major mechanical issue or natural disaster were to put the existing tube out of service for extended periods. At its busiest, the tube carries 28,000 passengers per hour, double the number of passengers traveling on the Bay Bridge, so there would be limited ability to handle commute flows if the BART tube were to fail.

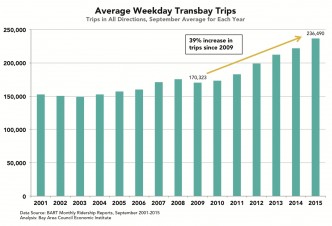

With ridership growing on all of the lines that feed into the transbay tube and with traffic on highway corridors throughout the region dependent upon BART’s performance, solving the transbay corridor bottleneck will play a key role in ensuring the region’s future economic resilience. Given the long lead-time required to plan and build infrastructure, the region has reached the critical moment when exploring options for a second transbay transit crossing is a necessity.

Analysis of a new transbay transit crossing comes as the region has undergone significant change over the last 50 years. BART was designed in the 1960s, when the Bay Area population was under 4 million people. Today, the Bay Area population tops 7.5 million and is projected to hit 9.3 million by 2040. A growing population is closely linked to a robust economy. Since 2010, Bay Area employment has grown at 3.2% annually, double the rate of peer US metropolitan areas.3 A thriving economy has brought with it increasing congestion on the region’s transportation systems, as more people are commuting to work and more trucks are on the roads making deliveries.

Locations throughout the region have been transformed completely by this growth. For example, the Mission Bay area of San Francisco was a field of underutilized rail yards when BART was opened, but now is home to a UCSF campus, has become an international center for biotechnology, and has a robust pipeline of infill housing office development projects. Downtown Oakland is also reaching a tipping point in its economic and population growth at a time when there is little spare core transportation capacity to accommodate such expansion.

Recent population and job growth have been important drivers of transbay transit capacity constraints, but there are other factors, including: a trend toward reduced car ownership; regional planning that targets and encourages growth around major transit hubs; job growth concentration in the urban core; and recent and future BART extensions that funnel more commuters into the transbay bottleneck. All of these factors continue to bolster BART ridership, putting more pressure on transbay capacity and reliability.

Yet with all this growth and change, the core BART system in place today looks very similar to the one that began operating in the 1970s. Longer and more frequent trains have been BART’s response to accommodate ridership growth, but the system will eventually hit a limit on its ability to respond in this way. New investment in core transportation infrastructure is the next step required to accommodate the region’s mobility needs and future transportation demand. The region’s ability to address this challenge in a strategic and expeditious manner will have important long-term implications for not only the Bay Area’s competitiveness and productivity, but its livability as well.

The Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), the region’s transportation planning agency, is studying several promising landing sites on both sides of the bay for a second transbay transit crossing as part of its Core Capacity Transit Study. One option, for example, includes a new BART tube connecting East Bay BART service, via Downtown Oakland and Alameda Island, with the existing San Francisco BART line, via Mission Bay and/or the South of Market area. A second option involves a new transbay rail tunnel that could be used by Caltrain and/or Capitol Corridor trains. This alignment would facilitate the delivery of High Speed Rail and could connect a new transit center in Downtown Oakland to the future Transbay Transit Center in San Francisco. While driven by capacity and reliability needs, these alignment options show that a second transbay transit crossing can create transformative transit connections, befitting the growth and dynamism of the Bay Area economy.

To begin a broader discourse on the economic case for a second transbay transit crossing and the financing models that could realize this vision, this issue brief

- summarizes the economic drag associated with current transbay transportation systems;

- describes several options under consideration for a second transbay rail crossing;

- identifies the benefits of addressing transbay transportation constraints; and

- describes how creative contracting and funding models could be leveraged to deliver a second transbay transit crossing in a timely manner.