Improving Individual Health Insurance Markets

In the U.S. health care system, the individual health care insurance marketplace has always been something of an afterthought. Most Americans of working age receive coverage through their employer. Older Americans and those with disabilities typically get benefits from Medicare. Fewer than one in ten Americans purchase coverage directly from statewide individual marketplaces, established through the Affordable Care Act, or purchase unsubsidized plans outside these markets. Nevertheless, this represents tens of millions of individuals who depend on the quality and choice of the products in the individual market.

The Individual Healthcare Marketplace: Always Needing Repair

The individual marketplace in most states was deeply troubled before the passage of the ACA. As one study in 2002 pointed out, “insurers underwrite aggressively, products carry high administrative loads, and markets are thin and volatile, with little competition. These problems exist across the span of regulatory environments, they are not easily solved, and policy alternatives…are not ‘magic wands.’” Though California’s marketplace was significantly more competitive than most, it still suffered from many of these difficulties, especially from health status underwriting, the use of an individual’s medical history to offer or deny coverage. The Affordable Care Act was an attempt to guarantee coverage at affordable rates to those in the individual market with preexisting conditions. It also tried to bring the relative stability and broader benefits of the large-group employer market to the individual and small-group marketplaces.

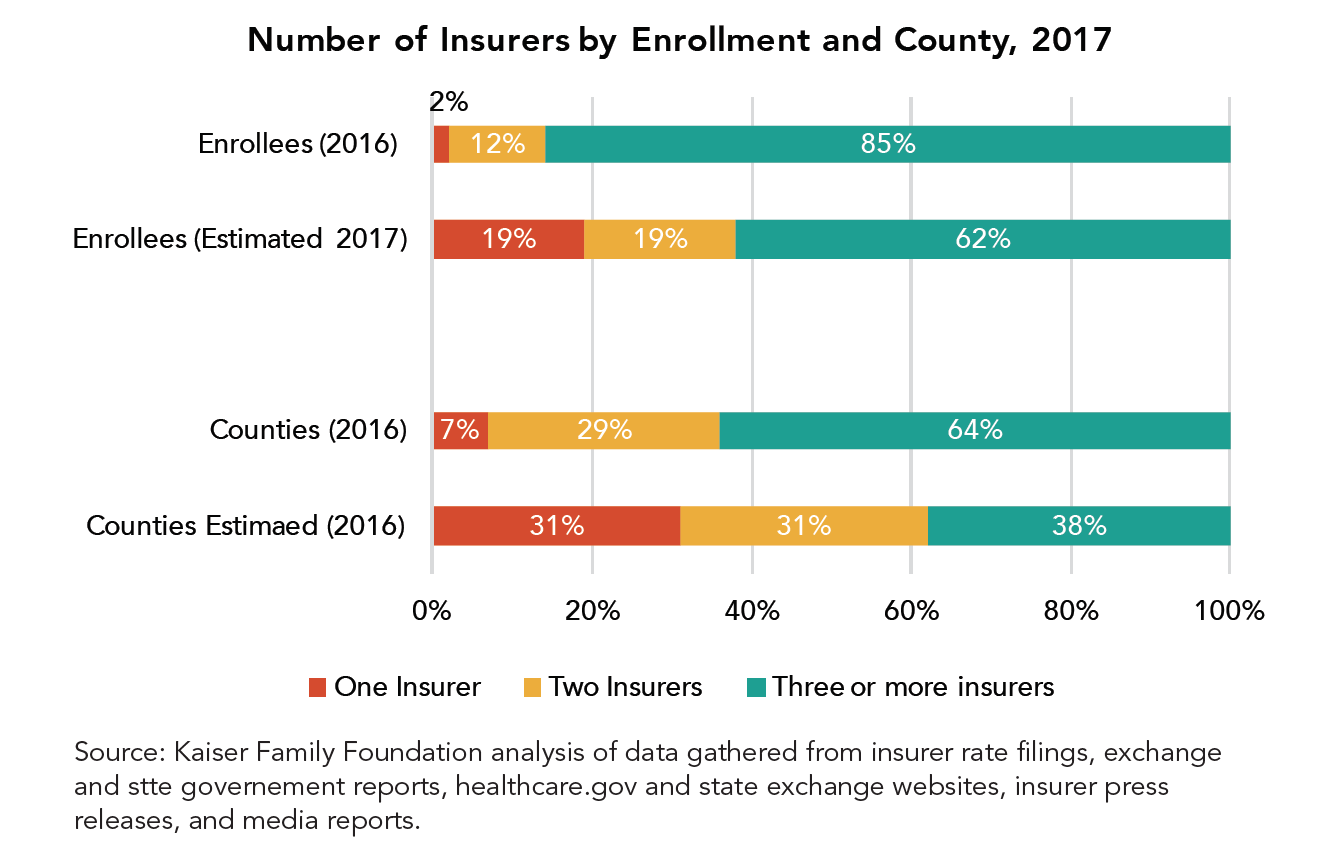

These goals have not been entirely realized. Premiums have continued to rise—by an average of 25 percent across all markets during the 2017 cycle. Major insurers such as UnitedHealth and Humana have left state marketplaces entirely or in part. Although no county will be without ACA coverage altogether in 2018, around seventy percent of the over 2000 counties in the U.S. will have three insurers or fewer participating next year. Moreover, insurers that have found relative success in the ACA marketplaces increasingly feature “narrow networks” of providers rather than the broader choice of doctors that most employees of large companies enjoy. Again, California has had a relatively better experience with significant market growth and smaller increases in rates than many other states. But the stability of the marketplace in this state and across the country have been handicapped by the ongoing changes at the federal level related to ACA implementation. The state recently added a surcharge to the cost of certain individual market plans in anticipation of the elimination of the Cost Sharing Reduction subsidies outlined in the law.

While the ACA is not collapsing, its individual marketplaces are far from steady. The withdrawal of plans and the limited choices facing consumers, as well as very high expenses for those buying insurance without subsidies, are likely to remain strong subjects of concern.

This report asks what steps could be taken to make the individual marketplaces more robust, stable, and affordable. Our emphasis is on policies that support a consumer-friendly marketplace in which insurers participate and are financially rewarded for providing value to consumers. This paper does not consider reforms, such as a return to aggressive underwriting, that might lead more insurers to participate in the marketplace and to do so more profitably, but that are inconsistent with what both Democratic and Republican legislators claim to want from this market, in particular affordable coverage for those with preexisting conditions. Health plan executives who were among the stakeholders and experts interviewed for this report are reluctant to return to the pre-ACA business model and market rules regardless of what the financial implications could be for their business.

Principles for Building a Better Individual Marketplace

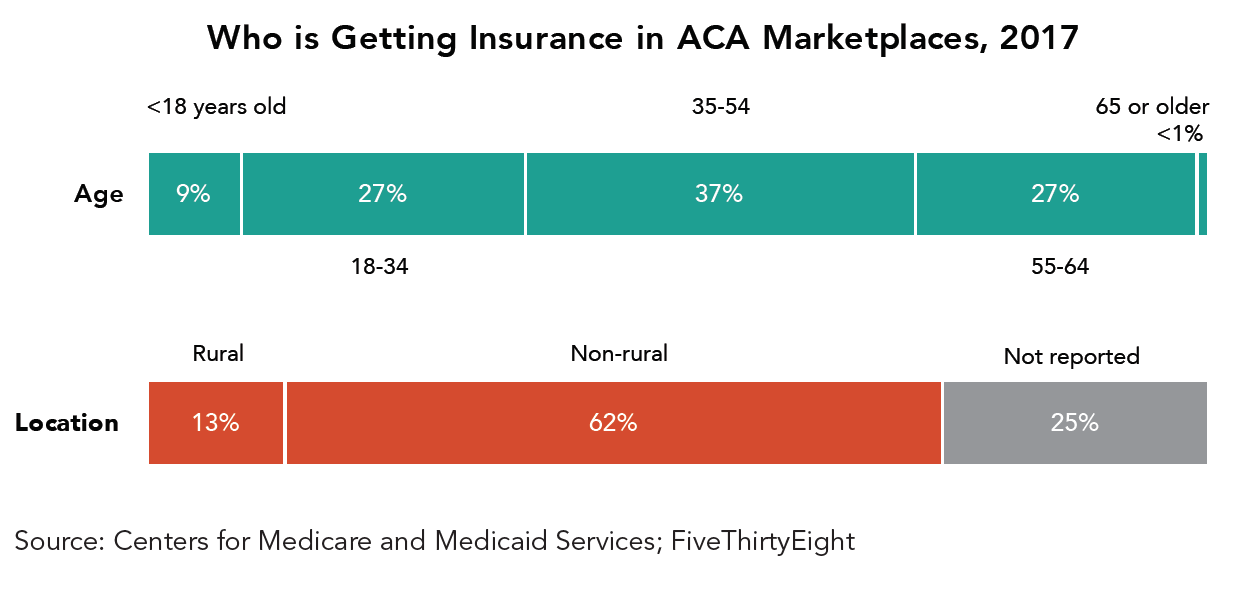

Unlike the employed population, which tends to be healthier and more similar in health risks, the individual market pulls together a set of people from very different backgrounds: the self-employed, who are often in good health; those employed part-time; those either near the beginning or end of their working careers; employees of smaller businesses that don’t offer employee or dependent coverage; people between jobs who cannot afford or access COBRA coverage; and some chronically ill Americans who do not qualify for Medicare or Medicaid.

Previously, the individual market had a much larger share of younger individuals in transition between jobs or seeking their first employer that offered coverage. In part due to the provision in the ACA allowing younger Americans to remain on their parents’ health plan until age 26, this proportion is diminishing. Relatively speaking, the numbers of middle-aged and self-employed Americans, and those nearing eligibility for Medicare, have been growing in recent years. In consequence, the pool of those purchasing in the individual market has become less transient.

What are the characteristics of a healthy individual health insurance market that serves these individuals?

There is majority agreement that a healthy market offers a range of options of health plans and products at an affordable total cost, including premiums and out-of-pocket costs. As in any private marketplace, participants can and should go out of business if they are not providing valuable products, but unlike in some other markets it is more important for there to be reasonable stability from year to year in terms of health insurers, since people rely on continuity of care. Every person who wants coverage, regardless of prior health history, should have an affordable plan available to them that provides access to a basic range of services.

There is also broad agreement that there should be strong incentives to be insured so as to avoid adverse selection, which can happen when people purchase coverage just when they need it and drop it when they don’t. Offering coverage to all comers while making it affordable implies that subsidies must be available for those who cannot easily afford a plan, and that some mechanism must exist to bring healthier individuals into the risk pool, whether through a requirement to purchase coverage (the individual mandate) or higher premiums charged to those with gaps in coverage.

The relatively small size and diverse population of the individual market means that changes to the population covered and the terms of that coverage will have an outsized impact on others in the same group. Expanding the current “risk bands” that limit the amount that insurers can charge based on age, for instance, will result on average in lower premiums for younger consumers and much higher ones for those nearing retirement.

Proposals to reform the individual health insurance marketplace inevitably confront the tradeoff between experience rating (in other words, a premium that reflects an individual’s own likely risks of needing care, including age) and community rating, which has the goal of reducing the variation in premiums in favor of those who need more expensive care. Before the ACA, when insurers practiced underwriting and those with preexisting conditions were unable to purchase coverage or were priced out of coverage, experience rating was the norm. After the ACA’s passage, community rating returned and many of those without a history of illness found themselves paying far more in premiums, frequently without federal assistance.

Stability of market rules

It is an underappreciated truism that a stable individual insurance marketplace requires consistent rules and regulations. Changing rules of the road have been the biggest challenge for health plans since the passage of the ACA. This is true both for established players and new entrants. Since the passage of the ACA in 2010, there have been many significant changes to the original rules. For example, while the Supreme Court decision that made the Medicaid expansion optional for states was welcomed by governors who by and large opposed the ACA, it altered the expected risk pools in those states. States that took up the Medicaid expansion have had better outcomes in their individual markets. Some policymakers lament the turbulence of these marketplaces but are at the same time primarily responsible for this turbulence through constantly attacking or changing the rules of the game.

One particular challenge is that the government has not consistently paid out the funds to insurers that were promised in the text of the law, notably “risk corridor” payments. These payments were among the three main risk mitigation strategies in the law. This non-payment was principally responsible for the demise of most of the new co-op insurers that had been set up by the ACA. A number of insurers have sued the federal government to recoup their payments. While two insurers, Molina and Moda, have been successful so far, the courts have ruled against insurers in three other cases, and the fate of these cases in the appeals courts is uncertain.

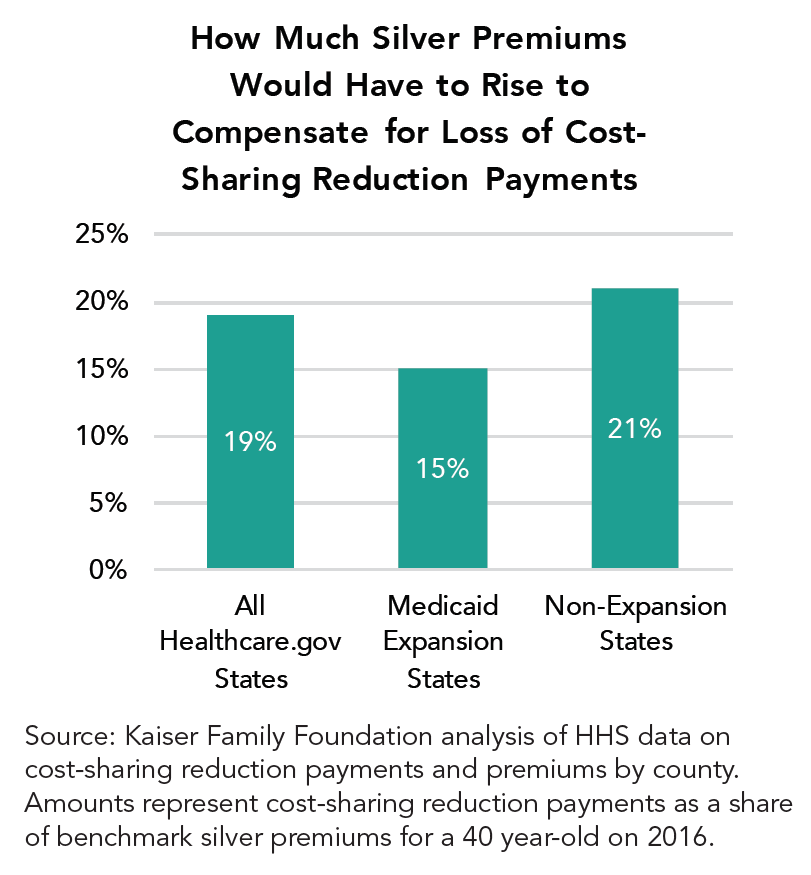

Insurers and regulators in practically every state and across party lines have made clear that the Trump Administration’s lack of clarity about whether it will continue to make Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR) payments was the single largest factor for the higher rates they requested for the 2017-18 plan year. They have highlighted this uncertainty as the reason for higher premium increases than they would have otherwise requested, which range from 15 to almost 100 percent in different plans in different states.

In November 2014, the House of Representatives sued the Obama administration on the grounds that it had not appropriated money to fund these CSR payments to insurers. These payments reduce the amount owed in out-of-pocket limits and cost-sharing by individuals and families with incomes between 100 and 250 percent of the poverty level who enroll in silver plans. Insurers are on the hook for the CSRs for individuals whether or not they receive the funds. After threatening for several months to end the payments, the Trump administration announced on October 12 that it would no longer fund CSRs. However, the future of these subsidies remains uncertain, as health insurers could sue the government for the payments, and there is some potential for a bipartisan Congressional solution that would fund CSRs.

In any case, not knowing the risks has prompted insurers not only to raise premium requests but to leave markets altogether. As Marguerite Salazar, the Colorado Insurance Commissioner, put it, “All carriers have expressed deep concerns about the increasing political and regulatory uncertainty around the individual health care market.” Joseph Swedish, the CEO of Anthem, which covers roughly one million ACA marketplace enrollees, recently remarked, “If we aren’t able to gain certainty on some of these items quickly, we do expect that we will need to revise our rate filings to further narrow our level of participation.”

Health insurers have had to operate in a rapidly shifting policy environment in which they cannot be sure that the market rules will remain consistent or whether funding promises from the government will materialize. Very large insurers have been able to dip into their reserves to cover the losses associated with this unexpected instability. Many smaller plans, including the co-ops, have gone out of business or have had to exit the individual market.

Any framework that “repealed and replaced” the Affordable Care Act with another system would have similar challenges in implementation should market rules or government funding guarantees change from year to year. It is crucial that policymakers understand that it is not the Affordable Care Act framework that has been the main challenge to the marketplace but rather a lack of willingness to commit consistently to the framework. Consistency and commitment are needed to produce better choices for consumers on the individual health insurance market.

Stewardship of the Marketplace

Each U.S. state puts in place safeguards designed to protect the stability of the health insurance marketplaces, such as financial standards boards for insurers. The serious question, therefore, is not whether there should be regulation but what the right level and type of regulation is, and what the relationship should be between health plans and regulators.

In the initial implementation of the ACA, there was a considerable degree of tension between health plans and their regulators across the country. This was particularly true in states that developed their own state-based exchanges. Health insurance executives were often barred from participating in the bodies that governed these marketplaces. However, after some start-up tensions, relations between insurers and regulators improved markedly. This was true even in states such as California, in which the pursuit of “active purchasing” allowed the exchange to exclude insurers from the marketplace as well as to negotiate prices and mandate benefit designs.

Both plan executives and public officials are stewards of the marketplace and must act in concert – while keeping their primary roles in mind – to support a healthy marketplace for individual insurance. This is true regardless of whether the policy framework going forward includes public exchanges. As an example of such successful cooperation, the unified efforts of regulators and health plan executives resulted in ACA coverage being offered in all counties in the United States for the 2018 plan year, a result that seemed very unlikely several months ago.

Tools for Building a Better Individual Marketplace

A number of policy and regulatory tools would improve the functioning of the individual marketplace. We take these up below, along with a handful of reforms that have been frequently proposed but are less likely to succeed. While fixing the root causes of the individual health insurance market’s instability might require slowing growth in overall health costs or absorbing the individual market into larger markets with better overall risk, most of these proposals would improve the function of these markets in the medium term.

Insurer-Focused Reforms

Preserving Cost-Sharing Reduction Federal Payments to Health Plans

The Trump administration has decided to stop making CSR payments, which represent a major obligation for insurers and figure prominently in their calculation of future premiums.

The Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that in the absence of CSR payments, insurers will have to raise their premiums by 19 percent on average for silver plans, though some increases will be much higher. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners and many insurers have written to Congress and the Trump administration warning of the massive disruption that a failure to fund this program will cause in individual marketplaces. They argue that the CSRs should be funded until there is an alternative policy in place or the underlying court case is resolved. Before the administration announced its decision, California, the nation’s largest marketplace, approved a CSR surcharge that health plans in the state may add only to their silver tier premiums in the event that the federal payments are terminated. This will place the majority of the cost primarily back on the federal government in the form of higher subsidies for individuals.

The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that terminating these payments will increase federal deficits, since premium increases will in substantial part be covered by higher premium subsidies for enrollees. Those who buy individual coverage without subsidies would bear the brunt of the cost of premium increases.

CSR payments were a relatively uncontroversial part of the ACA’s original design—the House lawsuit challenging their legality is principally about funding authority, not about policy––and are easy to calculate and straightforward to administer. Although some Republican lawmakers view the subsidies as a bailout for insurance companies, others have called for their continuation. Legislation currently under consideration in the Senate Health Committee and backed by the Republican chair and the ranking Democrat would preserve these payments for the upcoming year. This step would arguably do more than any other to stabilize the state marketplaces and the individual market in general in the short term.

Reinsurance, Risk Corridors, and Risk Adjustment

The Affordable Care Act contained various provisions designed to lessen the impact on the individual marketplace of moving from medical underwriting to guaranteed issue (the practice of charging the same premium regardless of an enrollee’s preexisting medical conditions). This move to a single-risk pool means that high-risk individuals may raise premiums for a group substantially by joining a particular plan. It also makes insurers more likely to engage in risk selection, the attempt to enroll healthier people rather than to compete on the value of services, or to be reluctant to enter markets because they worry that the health of participants may be worse than they predict. The ACA attempts to mitigate these issues through the “Three R’s”: risk adjustment, reinsurance, and risk corridors.

Risk adjustment transferred money from plans with lower-risk enrollees to those with higher-risk ones. Reinsurance programs made payments to health plans with higher than expected costs, allowing them to modify premium increases. Risk corridor programs temporarily reimbursed or charged plans whose claims fell short of or exceeded particular targets.

Medicare Part D prescription drug plans have achieved considerable success in stabilizing the Part D marketplace by using comparable plans, although these were more amply funded and of longer duration. While the ACA’s “Three R” programs were partly modeled on Medicare Part D, they have been less successful. This is largely because they were temporary, less well-funded, and—in the case of the risk corridor program, which was undercut by a refusal to appropriate funds for it—political opposition on the grounds that it constituted an “insurer bailout.”

Nevertheless, the reinsurance program has had substantial success in mitigating premiums in the marketplaces and successfully targeting insurers who had higher or lower claims than expected. For this reason, it has great potential both to improve the functioning of the individual marketplaces and to gain bipartisan support.

Health policy analyst Timothy Jost points out that “During 2014, the reinsurance program reduced net claim costs an estimated 10 to 14 percent, during 2015, 6 to 11 percent, and during 2016, 4 to 6 percent. The end of the reinsurance program after 2016 has been a major driver of premium increases for 2017 and 2018.” In recognition of this, the House’s American Health Care Act (AHCA), the Senate’s Better Care Reconciliation Act (BRCA), and health reform legislation introduced by Democrats and bipartisan groups in Congress all included reinsurance funds for the individual market.

Individual states have also used reinsurance programs to good effect in revamping their individual insurance markets. Alaska first instituted a program primarily using health plan dollars and then solicited the federal government with a waiver to seek federal funding to assist it. Minnesota has instituted a state-funded reinsurance plan to help insurers pay for enrollees whose costs exceed $50,000 a year, combining dollars from its general fund and a reserve health fund for low-income residents. These actions appear to be stabilizing premiums for the upcoming year and mitigating the effect of insurer pullouts.

Tightening the Rules of the Special Enrollment Periods (SEPs)

Historically the individual marketplace was dominated by enrollees who were in transition from one job to another or were on cusp of joining the workplace. While self-employment has risen and the ACA has opened up opportunities for longer stints of individual market coverage, the reality is that many individuals lose or change jobs, have children, get married, or experience other life events that change their eligibility between the annual open enrollment periods.

Insurers believe that some enrollees in SEPs have been gaming the system and do not qualify legitimately. As a result, they have built in premium increases to account for this behavior. The federal government has also taken action to address these concerns. Through a proposed rule issued by HHS on February 15th, 2017, and finalized on April 13, 2017, the agency will require pre-enrollment verification of eligibility as of June 2017 for most SEP categories in federally-administered marketplaces, affecting up to 650,000 individuals. Existing enrollees will not be able to change metal tiers during the year by using SEPs, to discourage the upgrading of coverage only when needed.

Although these changes are responsive to insurer concerns, it is unclear whether additional verification would actually deter sicker consumers. It might weed out, inadvertently, those presumably healthier individuals who are changing jobs and not signing up for coverage midyear because of the additional paperwork involved.

Changing Age Rating

The ACA limited how much older Americans eligible for the marketplaces can be charged for premiums, regardless of their higher utilization of health services. The maximum premium could be no more than three times that of the youngest enrollees. This is a lower ratio than had previously been used in most states.

This provision was intended to lower premiums for older Americans. Younger Americans were to be drawn into the insurance risk pool through the personal responsibility requirement (generally known as the “individual mandate”) and through subsidies to purchase coverage if their income level was low enough.

Relative to expectations, insurers in many states have attracted older enrollees and lower-income individuals who are eligible for higher subsidies, while younger and healthier customers either opt out altogether or purchase unsubsidized coverage outside the exchanges, where premiums are similar but networks of care are generally broader.

Potential responses to this adverse selection include raising subsidies for higher income enrollees or assessing higher penalties for not signing up for coverage. Since the mandate is generally unpopular, raising the penalty and enforcing the requirement more stringently is not considered a political option.

Another option is to relax the age band ratios in an attempt to lower premiums for younger and healthier customers and to induce them to take up coverage. The AHCA passed by the House would allow states to raise the age rating ratio from 3:1 to 5:1. This could, in theory, stabilize certain markets by drawing in a greater number of healthier individuals, but it might also price some older enrollees out of coverage altogether. If young people continue to be covered on their parents’ plans, are more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid, or are more likely to qualify for low-income subsidies, this reform would be less attractive in terms of stabilizing markets.

Selling Insurance Plans across State Lines

During his presidential campaign and during his first address to Congress, President Trump promoted the idea of selling insurance products across state lines, “Creating a truly competitive national marketplace that will bring cost way down and provide far better care.” His October 12th executive order directing the Labor Department to seek ways to facilitate the creation of Association Health Plans (AHPs) likewise supports the goal of making it easier to purchase health insurance across state lines.

This idea has been a staple of GOP presidential campaigns in the past and is featured in a number of GOP plans, such as Speaker Ryan’s “A Better Way” plan and former HHS Secretary Tom Price’s “Empowering Patients First Act,” promulgated when he was a House member from Georgia.

The three main challenges to this approach are insurer motivation, risk selection between states, and protection of consumers. Under the ACA, insurers are already permitted to sell across state lines, though under a stricter set of rules than most of the GOP plans envision. The main reason they do not is because of the challenge of building networks of doctors and hospitals from scratch. This is difficult even for well-capitalized market entrants with local ties, and much more difficult and expensive for companies trying to obtain licenses, build networks, and find customers from afar.

Another roadblock is the lack of room for competition between states as a result of the essential health benefits mandated by the ACA. Regulations for insurance are largely the same in each state, so plans are fairly uniform. This means insurers have little flexibility to compete on what their plans cover between states, or for states to compete on their regulations.

Conversely, if regulations regarding essential benefits were relaxed, consumers buying across state lines would seek plans with lower premiums, likely reflecting policies that didn’t offer certain benefits such as maternity services. However, over time, this process could yield a “race to the bottom”: a high concentration of healthy groups covered under one state’s regulations and sicker ones in others, resulting in unaffordable premiums and worse benefits in states that chose not to relax their regulations.

Finally, it is unclear that consumers in out-of-state plans would have any real recourse in disputes against their insurer, since it is unlikely that they would get attention from state insurance departments without being residents.

Continuous Coverage

Any health insurance marketplace that allows guaranteed issue must include some mechanism to dissuade individuals from choosing to seek coverage only when they are ill. This “free-rider” problem leading to an insurance death spiral has cropped up in New York, New Jersey and other states that have experimented with guaranteed issue without such counter-weights.

The AHCA bill passed by the House of Representatives sought to address this issue by assessing a premium surcharge on individuals who had a gap in coverage, specifically a 30 percent surcharge on any individual not insured in the previous twelve months. (The BRCA in the Senate lacked such a measure, presumably because its authors wanted to avoid coming into conflict with special Senate rules on passing a bill through reconciliation.)

Using the continuous coverage test as a method to encourage enrollment would be desirable if it led to increased enrollment in marketplaces and lowered premiums. Whether such provisions would accomplish this goal is unclear. The CBO estimated that this policy would provide an early boost to enrollment but would result in about 2 million fewer people purchasing coverage over time, as healthier people choose to skip coverage altogether and face no penalty for doing so.

A problem with continuous coverage provisions is that they could easily dissuade Americans with less knowledge of health options and with challenging circumstances from enrolling in the first place. By contrast, seniors who delay enrolling in Part B of Medicare face a similar penalty but as a group are far more familiar with Medicare and its rules. One way to address this concern could be to auto-enroll Americans in high deductible plans that would simultaneously satisfy the problem of interrupted coverage while offering some protection against catastrophic health care costs.

State-Focused Reforms

High Risk Pools

Prior to the adoption of the ACA, thirty-five states operated high risk pools, which serve to separate those with high-cost and preexisting medical conditions from the rest of the individual markets.

Proponents of reviving high-risk pools, such as Paul Ryan, believe this strategy lowers premiums and vastly improves the risk profile of the individual market. The transparency of government payments for those in the pools is perceived as another positive, along with the fact that government as a whole rather than the remaining group covers the costs of high risk individuals (although a well-designed program of government-funded reinsurance could probably accomplish similar results).

Indeed, a number of analysts believe that the problems of the individual market stem from merging the former high-risk pools into the broader marketplace and, more generally, in choosing to end medical underwriting.

While segregating high-risk enrollees into separate pools unquestionably lowered premiums for the remainder of the marketplace, the overall experience of enrollees in those high-risk pools tended to be very poor. Generally, they confronted high deductibles, low annual spending caps, coverage exclusions, and high premiums.

Moreover, virtually every one of the pools was chronically underfunded and, as a result, chose either skimpier coverage or instituted enrollment caps. The temporary high-risk pool instituted by the ACA (the PCIP) experienced similar problems. The dollar amounts floated to fund such pools in the recent debates appeared to be far short of what would be needed to assure high- quality, affordable coverage.

Invisible High-Risk Pools/ Prospective Risk Adjustment

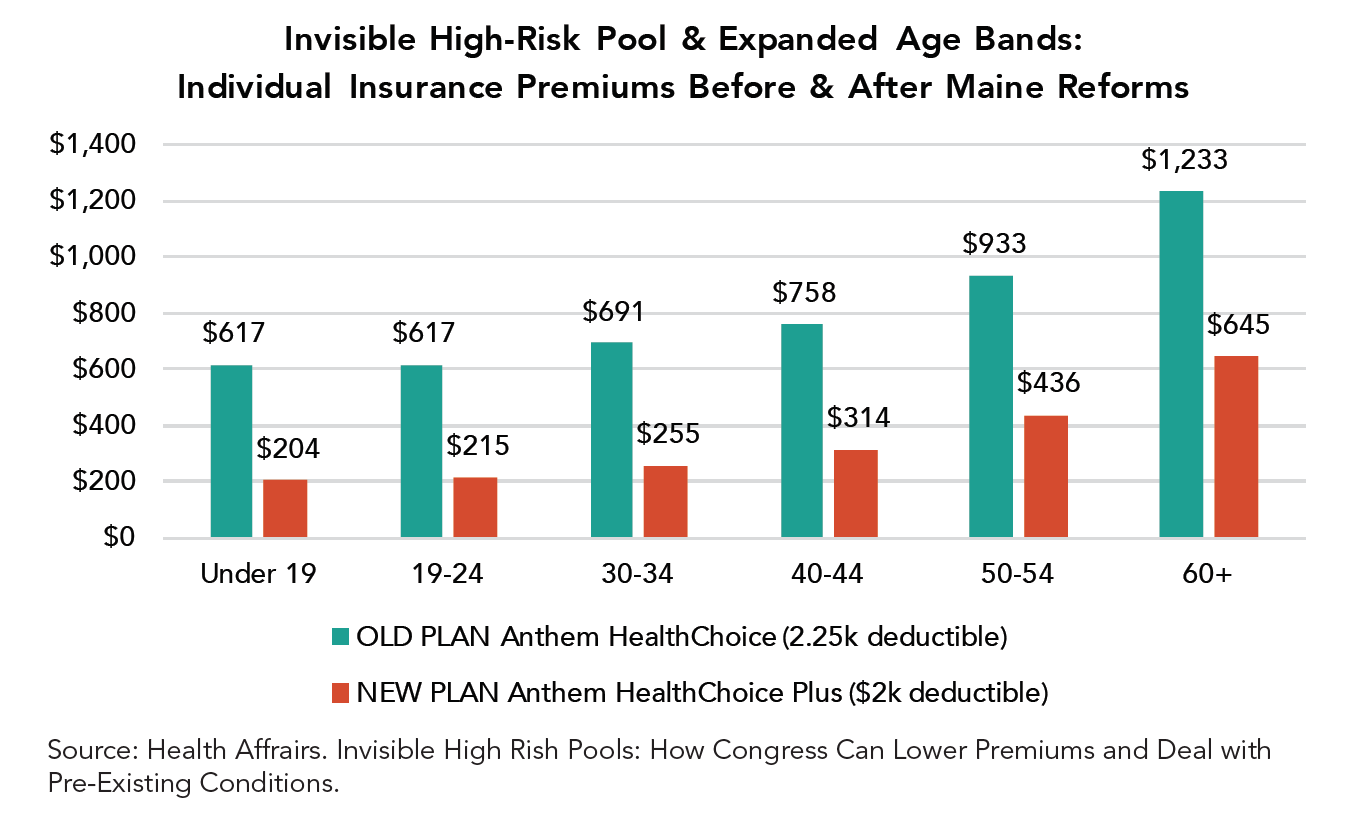

One intriguing strategy to lower premiums in the individual market is the concept of an invisible high-risk pool, a combination of a high risk pool and reinsurance. In conjunction with relaxed age rating and other changes, this idea is credited, in 2011, with reversing a “death spiral” in Maine’s individual insurance market.

Under “invisible” high risk pooling, everyone applying for insurance fills out a statement about their existing health conditions, but unlike medical underwriting all applicants are placed in the same plan they apply for and pay the same rates. Insurers place high-risk individuals in a separate pool (which applicants are unaware of, thus “invisible”) and transfer most of their premiums to an entity that manages the program. In Maine, the remainder of the financing for the pool was raised by a levy on all health insurance policies.

The strongest argument for invisible high-risk pooling is that it may perform better than traditional reinsurance at identifying potentially expensive enrollees and consequently allow insurers to offer lower premiums and to attract a healthier mix of enrollees to the remaining pool. On the other hand, it is labor-intensive, complicated, and doesn’t effectively deal with individuals who incur expensive health conditions after joining a plan. It may be useful in some state markets and less applicable to others.

Liberalizing the ACA’s 1332 Waiver Process

In 2017, a provision in Section 1332 of the Affordable Care Act took effect. This measure permits states to seek a waiver from the Secretary of Health and Human Services in order to test alternative approaches to providing affordable health insurance coverage. These alternatives cannot result in higher federal costs. Nor can they change certain other critical features of the ACA, such as providing insurance coverage less comprehensive than the essential health benefits required of all plans.

Using 1332 waivers to stabilize state individual marketplaces has become an increasingly prominent goal of states, especially after ACA “repeal and replace” legislation failed to advance. This process has taken two distinct forms. In the first, several states have sought to use waivers to establish reinsurance programs, as noted above, that would allow the state to absorb the cost of high-cost patients and pay for this by recouping savings generated by lower federal subsidies for premiums in the marketplace.

Despite a March letter from the Trump administration encouraging governors to submit waiver proposals for reinsurance programs, this process has been bumpy. Alaska, Minnesota, and Oregon have received approvals for at least the reinsurance elements of their proposals, while Oklahoma—despite following a similar procedure and claiming that it had received reassurances of speedy action—withdrew its application after the waiver wasn’t granted in time to meet the deadline for insurers to finalize marketplace rates.

Putting aside the merits of Iowa’s particular case, either in its assessment of the marketplace or the merits of setting aside statutory authority, there is a good case to be made for streamlining the waiver process and allowing states more flexibility to make changes to the structure of their markets. However, assessing its value also depends on the particular goal this flexibility is likely to serve (most likely reducing the set of essential benefits, the allowable actuarial value of plans, and allowable out-of-pocket costs, for instance) and whether it is appropriate under the specific circumstances facing that state.

The other track involves changing the terms of the waivers so that states will have latitude to change more fundamental features of the ACA or to get streamlined approval from HHS for taking steps that resemble those approved in other states. Iowa, for example, has requested a waiver that would replace premium tax credits with a flat credit and eliminate the ACA’s cost-sharing reductions. The BCRA and the America Health Care Freedom Act included language that would widen the scope of potential waiver requests and give the Secretary of HHS less discretion to deny them. Likewise, the Alexander-Murray bipartisan proposal would make it easier to obtain 1332 waivers.

Putting aside the merits of Iowa’s particular case, either in its assessment of the marketplace or the merits of setting aside statutory authority, there is a good case to be made for streamlining the waiver process and allowing states more flexibility to make changes to the structure of their markets. However, assessing its value also depends on the particular goal this flexibility is likely to serve (most likely reducing the set of essential benefits, the allowable actuarial value of plans, and allowable out-of-pocket costs, for instance) and whether it is appropriate under the specific circumstances facing that state.

Consumer-Focused Reforms

Expanding HSAs and HRAs

Current law does not allow high-deductible plans purchased through the marketplaces to be paired with a Health Savings Account (HSA), a widely-used vehicle in employer-based coverage that allows enrollees to make contributions that are excluded from income tax and to receive distributions tax-free so long as they are used to meet certain medical expenses.

The main challenge to HSAs is that they primarily are useful only to those with money to invest—indeed, some seventy percent of HSAs are held by those with annual incomes of $100,000 or more—and that consumers do not discriminate in spending the proceeds between care that is of high or low value. Nevertheless, gaining access to HSAs would offer some relief to individuals who buy ACA plans on the exchange and ACA-regulated plans outside the marketplace, a group which has been greatly impacted by rising premiums.

Changing Essential Benefits

Reducing coverage of the essential health benefits mandated under the ACA would definitely reduce premiums in the remainder of the marketplace. This is a pretty straightforward trade-off, since those requiring coverage (maternity coverage being the most salient) would pay much more for their premiums if currently required EHBs were pared back.

Consumers who require coverage for fewer types of benefits would likely move to less comprehensive plans, and those who expect to need benefits like maternity or mental health coverage would increasingly be the only ones who purchased the more generous, more expensive plans, further increasing the risk of insuring that pool and driving premiums up even higher.

The Urban Institute recently calculated that the EHBs covered under the ACA and most commonly cited in repeal legislation (maternity and newborn care, rehabilitative care, and pediatric dental and vision care) account for less than 10 percent of the monthly premium. Should the cost of these services be covered under insurance only by those who needed them, the researchers estimated that their premiums would rise by an average of $13,888 annually. Scaling back EHBs would raise costs to those who are most likely to be economically vulnerable.

Making Subsidies More Generous

Currently, under the ACA, those who purchase insurance on the individual exchanges with incomes between 100 and 400 percent of the federal poverty line may be eligible for the premium tax credit. The amount of the credit varies; those with lower incomes and those who live in regions where individual market plans are more expensive receive larger credits. While most legislation from both sides of the aisle emphasizes uniformity in the provision of refundable tax credits, it might make sense to revise the rules so that those in higher-cost areas, with lower incomes, or older and needing more assistance received increased resources. Subsidies for the most economically vulnerable could be made more generous and more specifically targeted.

For example, Avik Roy proposes that health care reform bills could improve the market by varying tax credit amounts based on a combination of age, health, and income. Adding more dollars in the context of an explicit funding formula, he argues, is fundamentally different from dispensing money to aid in a current health crisis or to a particular state whose legislator’s vote is needed. Such targeted assistance in the context of higher spending would be a promising way to stabilize markets under a variety of legislative proposals.

Another option for increasing subsidies, proposed by Jodi Liu and Christine Eibner of the Commonwealth Fund, is to extend eligibility for premium tax credits to those with incomes above 400% of the poverty line who do not have another affordable source of coverage. Their study projects that doing so would increase health insurance enrollment by 1.2 million. These new enrollees would primarily be healthier, so their entrance into the individual market would potentially lower premiums and improve the risk pool.

Conclusion

Tens of millions of Americans rely on the individual market for their health insurance. Though these marketplaces provide good, affordable coverage to many, they are also in need of repair. Premiums continue to rise, and several major insurers have left state marketplaces.

A healthy market will need to provide quality products at an affordable cost, and it must be stable from year to year. Some potentially promising tools to maintain and improve the marketplaces include, among others, preserving cost-sharing reduction federal payments, implementing reinsurance programs, liberalizing the 1332 waiver program, expanding HSAs and HRAs, and raising tax credits for certain groups of Americans. Whichever approaches might be chosen, it will be very important to reduce uncertainty about the future of the marketplace for both insurers and consumers.