Economic Profile 2020: The Evolution of the Bay Area Higher Education System in the Wake of COVID-19

How will the Bay Area’s higher education system evolve post COVID-19?

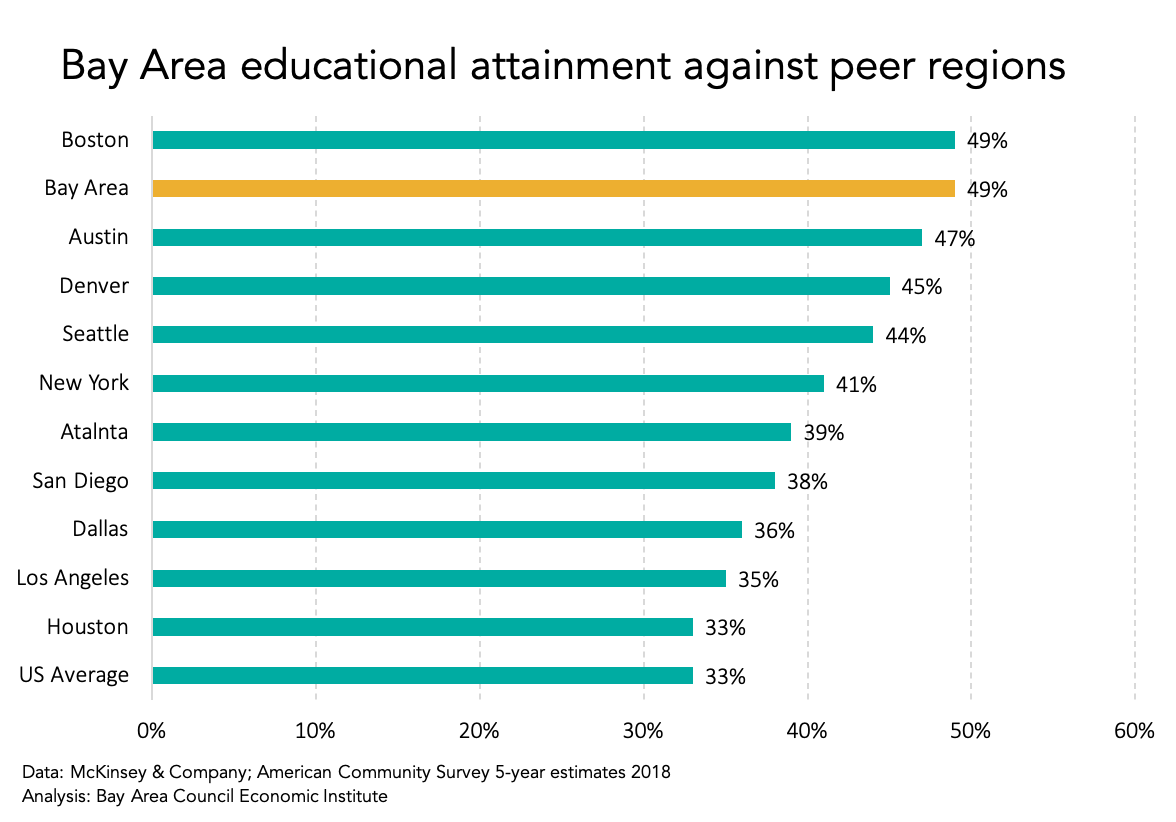

With 49% of the population over the age of 25 holding a bachelor’s degree, the Bay Area has one of the most highly education populations in the nation. This level of educational attainment is matched only by Boston (also 49%) and is well above the 33% national average. The region is also home to several institutions making impressive research investments. UC San Francisco (3), Stanford (10), and UC Berkeley (26), all rank within the top institutions nationwide in terms of expenditure on science and technology R&D. Additionally, MBA and undergraduate degree holders from Stanford and UC Berkeley have started impressive numbers of companies backed by significant venture capital. According to an analysis of Pitchbook by McKinsey & Company, between 2009 and 2017 Stanford and UC Berkeley graduates started a total of 2,948 companies. The region also has five different California State University campuses and an array of community colleges.

The continued strength of the region’s higher education institutions is a key input to the vitality of the Bay Area economy. These campuses produce entrepreneurial graduates and support significant investment in R&D, which are two integral inputs to the innovative nature of the Bay Area economy that drives economic growth in the region.

As these institutions grapple with the impacts of COVID-19, their future trajectories remain at least partially unknown. Revenue concerns driven by uncertain levels of enrollment, the possibility of partial or full remote teaching, and changes in first-choice school preferences among incoming students are all variables that could reshape higher education in the Bay Area in the wake of the virus.

Exhibit #1: Can the Bay Area make progress on racial disparities in educational attainment?

Compared to major regions across the country, the Bay Area leads the nation in terms of the share of people who hold bachelor’s degrees. However, examining educational attainment among racial and ethnic groups shows wide disparities in the share of Bay Area residents age 25+ who hold bachelor’s degrees. Only 28% of Black and 18% of Latinx Bay Area residents over the age of 25 hold a bachelor’s degree, compared to 46% bachelor’s degree holders among 25+ white residents.

Admissions, enrollment, and college completion rates in California all show racial and ethnic inequities:

Admissions: While progress has been made in recent years, the UC admissions rate for Black applicants in 2016 was still only 47% compared to 62% among white applicants.

Enrollment: Only 3% of all Black students enrolled in post-secondary education institutions in the state in 2016-17 were enrolled at UC colleges, compared to 6% of white students. Black students were more likely to be enrolled at a community college, with 72% of Black students enrolled in a post-secondary institute at community colleges (68% of white undergraduates).

College Completion: College completion rates for Black students lag behind the comparative rate for white students. The six-year completion rate at UC colleges is 75% for Black students compared to 86% for white students; 43% compared to 37% at CSU campuses; and 37% compared to 54% at community colleges.

The drivers behind this inequity in post-secondary education enrollment and completion are dependent on many factors that occur earlier on in the educational system. In particular, inequities in school funding can impact the readiness of graduates for post-secondary education.

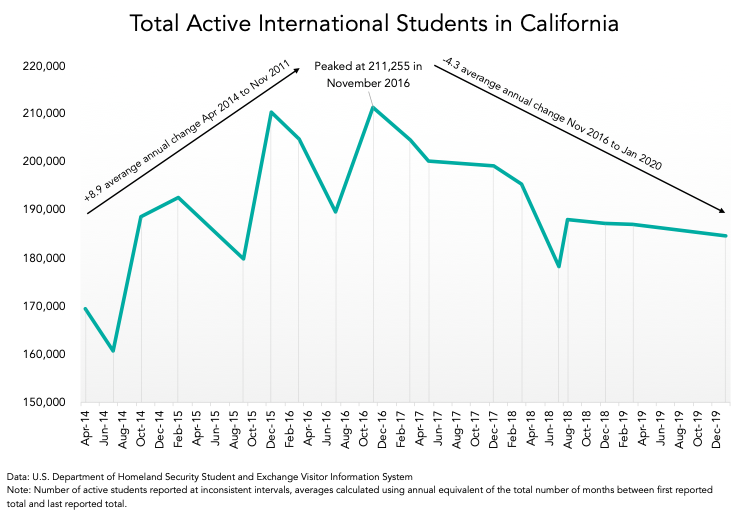

Exhibit #2: What impact would lower levels of international student enrollment have on Bay Area higher education institutions?

According an analysis by the National Foundation for American Policy, the enrollment of new international students is projected to decrease from 2018-19 levels by between 63% and 98% in 2020, based on current border restrictions due to COVID-19. Home to the largest number of international students out of all U.S. states, many California institutions would be particularly impacted by a decline in new international student enrollment. International students make up 14.4% of the UC system’s overall enrollment, so a lasting decline could have significant impacts on the student population. In the Bay Area, schools such as UC Berkeley and Stanford University that contribute to the unique strength of the economy traditionally host thousands of international students.

Exhibit #3: How will university R&D investments shift in the wake of COVID-19?

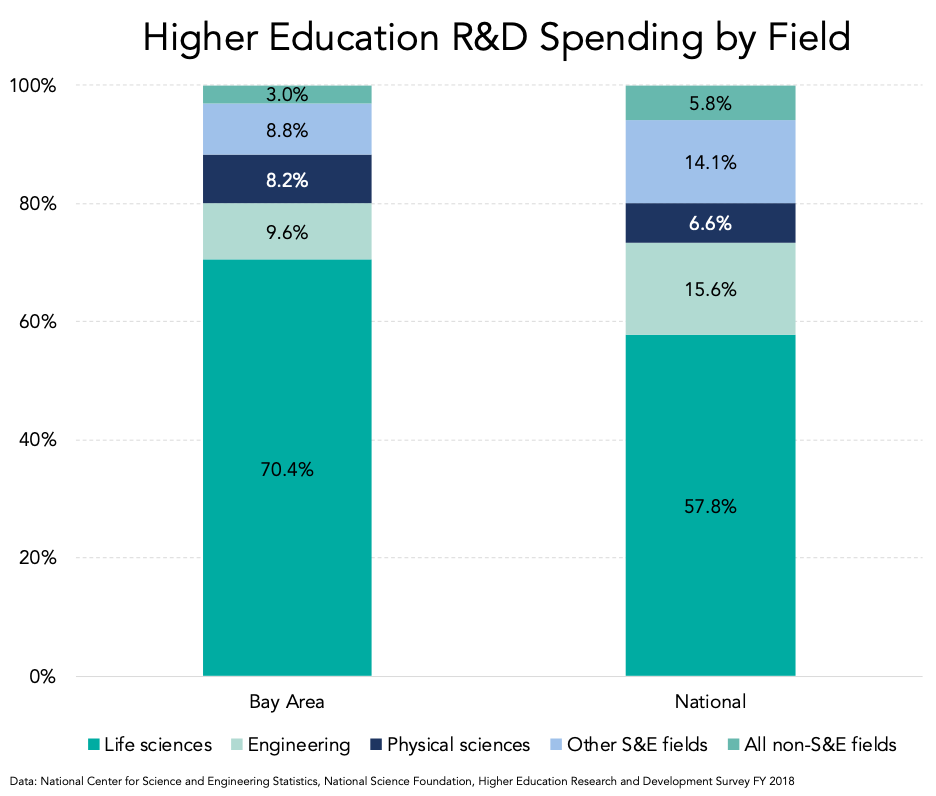

The university systems of the region are also major contributors to research and development (R&D), particularly in the life sciences. While certain life sciences R&D labs are kicking into overdrive with the vital goal of developing a vaccine or treatment for COVID-19, other subsections of the field and non-life sciences R&D fields face challenges in continuing their course amidst the implications of the virus. Surveys have shown that R&D organizations estimate productivity has fallen between 25 and 75 percent due to remote work, likely a factor of operating capacity being reported as 50 percent below normal.

Reduced operating capacity, supply chain disruptions, and laboratory shutdowns all have implications on the short-term productivity of product development, engineering, clinical trials, and more. Uncertainty around future market and customer demands further impact the ability of R&D organizations to prioritize programs and resourcing.

Compared to the breakdown of higher education R&D spending by field at the national level, the Bay Area has an over representation of spending in the life sciences field, with two-thirds of higher education R&D spending concentrated in life sciences as of fiscal year 2018. This concentration in life science R&D is a clear strength for the region, and it can be linked to the rapidly growing biotech industry in the Bay Area. With much of this R&D funding coming from state and federal grant programs, constrained public sector budgets in the wake of the pandemic could hamper spending levels going forward.

Conclusion

As the region begins to recover from the economic fallout of the pandemic, ensuring the strength of the Bay Area’s higher education institutions and maintaining the comparatively high level of educational attainment in the region are both integral inputs needed to protect the long-term vigor of the regional economy. As such, keeping an eye to factors such as equity in educational attainment, barriers to international enrollment, and changes in R&D spending is important during this period of recovery.