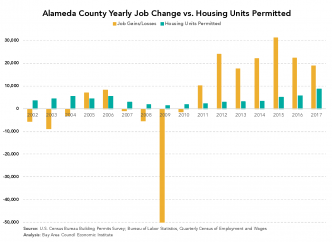

The housing affordability crisis in the Bay Area is having ripple effects across our economy. Renters are looking for housing further from economic centers in search of affordability, resulting in long, time-consuming commutes. Businesses across all industries are struggling to attract and retain workers as the cost of living rises. Even existing homeowners are seeing their children and grandchildren pushed out of the region.

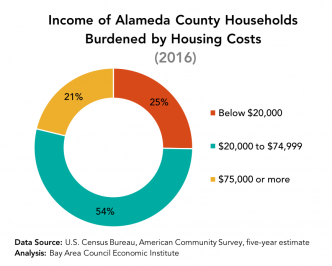

High housing cost burdens fall most heavily on lower-income households. A recent report by PolicyLink and the USC Program for Environmental and Regional Equity found that a family of two workers, both making minimum wage, can afford the median market rent in just 5% of Bay Area neighborhoods. Of those neighborhoods, 92% are rated as having very low economic opportunity, which further stifles economic mobility and jeopardizes the region’s future success.

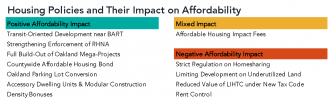

This report digs into the policies that would improve or worsen housing affordability for families in Alameda County. To help policymakers focus on real solutions to the housing crisis, we compile a list of 20 housing-related state and local policies—some that have been implemented and others that have only been considered—and analyze their impacts on net affordability, measured in the number of households that move above or below a 30% housing cost-to-income ratio.

The analysis that follows uses the same methodology employed in our October 2016 report on housing affordability in San Francisco. The geographies are different, but the conclusions are largely the same:

1. Policy does matter.

While demand has been the leading cause of high housing costs in Alameda County, we show that local housing policies also have considerable effects on affordability. In Oakland, reducing parking requirements can move 1,339 households into a more affordable situation. Quicker completion of Oakland’s four mega-projects would have an even bigger effect of 2,967 households. On the opposite end of the spectrum, a failure to build on Alameda Point has meant that 1,620 households in the county live unaffordably. Broad rent control across the county would have even further negative effects on overall unit production, prices, and affordability—10,353 households would lose affordability under more strict rent regulation.

2. Building all types of housing is still the best way to alleviate housing cost burdens.

In order to truly address the housing affordability crisis, the region needs more housing units overall to both make up for decades of under-production and to meet present and future demand. Of the most positively impactful housing policies that we analyzed, those that focus explicitly on building more rapidly were the most positively impactful. For example, the completion of transit-oriented developments near BART (improves affordability for 7,192 households) and enforcement of regional housing goals (improves affordability for 4,494 households) would both have significant positive effects on affordability in the county through the provision of more units.

3. Supply alone will not help the most vulnerable households.

Units that are explicitly rented below market rates or that are affordable by design (e.g., micro-units or accessory dwelling units) contribute directly to a lower housing cost burden for the families that reside within them. In addition, the county’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund approved by voters in Measure A1 in 2016 provides $425 million for below-market-rate housing development, which will move 4,064 households into an affordable housing cost burden.

4. Producing market rate and affordable housing goes hand in hand.

In order to reduce poverty, combat climate change, and improve the quality of life, more housing is needed for people at all levels of income. This is sometimes framed as a zero-sum contest between market rate and affordable housing. But the factors that make market-rate housing more difficult, expensive, and time-consuming to produce are those that have led a door of “affordable” housing costing nearly $420,000 to produce. The best solutions maximize the production of both market-rate and affordable housing.

5. We’re all in this together.

Solving the housing affordability crisis is not an Oakland issue and it is not a Berkeley issue. It is an every city, every neighborhood issue. This report evaluates policies in Hayward, Union City, Livermore, Fremont and elsewhere that could have a positive or negative affect on affordability. Ultimately, this is a crisis that needs to be addressed at the level of the region (or even the state) with policies that support the creation of housing for people at all income levels in all nine counties. The solution is not going to look the same in Castro Valley as it is in Uptown in Oakland, which makes state, county, and regional policymaking even more important as key ways to lift up the best local policies. Each jurisdiction needs its own plan to help accommodate the region’s growth, but every city also needs to be on board to address this collective challenge.

If all of the positive housing policies analyzed here were enacted, just over 26,000 households would move into an affordable situation (or about 12% of the housing-cost burdened population in Alameda County). While these policies would not fully solve the housing affordability problem in Alameda County, we do find that good policy choices can play a critical role in housing affordability. We have identified policy benefits, trade-offs, and unintended consequences—all of which should be carefully considered as the county and its cities work to address the housing affordability crisis.